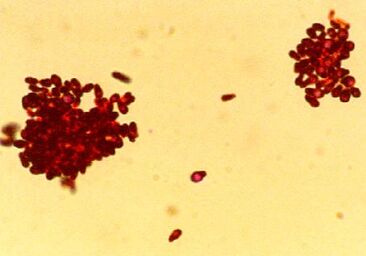

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Malassezia pachydermatis organisms. CDC/Janice Haney Carr. Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Malassezia pachydermatis organisms. CDC/Janice Haney Carr. Yeast skin infection (dermatitis) is common in dogs and also affects cats. Animals with allergies to pollen, grass, and other substances are especially prone to yeast dermatitis and yeast ear infections, so watch for the signs of infection if your pet gets itchy when the seasons change. Causes Yeast dermatitis is caused by Malassezia organisms on the skin. Malassezia yeasts are part of the normal collection of microorganisms that live on the skin and in the ears of animals. Yeast dermatitis occurs when something about the host animal—skin condition or immune function—causes Malassezia to overgrow or results in an abnormal immune response to Malassezia organisms. Examples of skin conditions that lead to yeast overgrowth are inflammation and increased moisture. Some animals are allergic to Malassezia and develop yeast dermatitis even when the number of organisms on the skin is relatively low. These are some of the things that increase the risk of yeast dermatitis:

Signs The most commonly affected areas are the face, neck, armpits, belly, inner thighs, feet, and ears, although yeast dermatitis can affect any part of the skin. Yeast dermatitis typically causes these signs:

Diagnosis Samples from affected areas are taken with various methods (tape pressed to the skin, a microscope slide pressed to the skin, cotton swabs, scraping with a blade, or possibly skin biopsy) and examined under a microscope. Animals with yeast dermatitis might have very few Malassezia organisms visible with a microscope. In animals with long-term or recurring yeast dermatitis, other tests are often done to look for an underlying cause. Treatment Yeast dermatitis is treated with topical medication, oral medication, or both. Topical antifungal products include shampoos, mousses, wipes, creams, and so forth. Topical products need enough skin contact time to be effective, so shampoos usually come with instructions not to rinse the lather off for at least 10 minutes. A number of prescription oral antifungal medications are also used. The choice of treatment type—topical, oral, or both—depends on the individual animal, the part of the body affected, the response to earlier treatment, and the ability of the animal’s owner to apply topical treatments. Not everyone has a place to bathe a large shaggy dog twice a week, for instance. Treatment for yeast dermatitis typically needs to continue for weeks. For animals with recurring yeast dermatitis, the underlying cause also needs to be treated. Reference 1. Bond R, Morris DO, Guillot J, et al. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol. 2020;31(1):28-74. doi:10.1111/vde.12809 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/vde.12809 Public domain image source: CDC/Janice Haney Carr Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Ezequiel Garrido Photo by Ezequiel Garrido A cataract is an opacity in the lens, a small translucent structure just behind the pupil of the eye. The lens transmits light to the retina at the back of the eye. Because cataracts block light from reaching the retina, they can cause blindness. In some cases cataracts also lead to eye pain. Cataracts are most common in older animals but also occur in young animals. An animal can have a cataract in just 1 eye or in both eyes at the same time. Cataracts begin as small opacities that don’t have much effect on vision; the animal can see around them. Over time, some cataracts progress to involve most or all of the lens, reducing vision. Cataracts commonly cause uveitis, or inflammation inside the eye. Uveitis can be uncomfortable. Cataracts can also cause lens luxation (lens slipping out of its normal position). Lens luxation increases the risk of glaucoma, which is painful and can also cause blindness. Nuclear sclerosis of the lens is a normal aging change that looks similar to cataracts but doesn’t cause blindness or inflammation. The lens becomes more dense with age. In older animals, increased lens density makes the lens look cloudy, so the pupil appears bluish-gray instead of black. Unlike cataracts, nuclear sclerosis doesn’t block light, so it doesn’t interfere with vision. Causes Cataracts in dogs are often hereditary. Some of the many dog breeds that have hereditary cataracts are poodles, Havanese, Boston terriers, silky terriers, and cocker spaniels.[1] Animals with hereditary cataracts should not be used for breeding. Cataracts can also be caused by other conditions. Diabetes is a common cause of cataracts. Owners of a diabetic animal should know that their pet might go blind from cataracts. Cataracts can also be caused by trauma, inflammation, aging, toxins, and malnutrition. In many cases, the cause is not known. Symptoms An animal with a cataract usually has no symptoms (other than the opacity in the lens) unless the cataract blocks vision or causes uveitis. The signs of vision loss can be very subtle in animals, especially pets that live in environments that don’t change very much. Indoor pets know their way around the furniture and might not start bumping into things until they are nearly blind. Reluctance to jump up, navigating stairs more slowly than usual, and having a hard time finding food or the water bowl can be signs of impaired vision—or of other problems like arthritis. The signs of uveitis caused by cataracts are also subtle and easy to mistake for other eye problems. Redness, drainage or discharge, and squinting are signs of eye discomfort from any cause. An animal with these signs should be checked by a veterinarian without delay. Diagnosis Examination of the eye with an ophthalmoscope is used to diagnose cataracts, distinguish between cataracts and normal nuclear sclerosis, and look for uveitis and other problems within the eye. Blood and urine tests are used to diagnose diabetes and other conditions that can cause cataracts. Treatment Small cataracts that don’t cause vision loss might not need to be treated right away, but they should be monitored. Even small cataracts can cause uveitis, and the earlier uveitis is treated, the better for the patient. Cataracts are treated either medically or surgically. The aim of medical treatment is to keep the eye comfortable by managing inflammation and other complications. No known medical treatment can prevent a cataract from progressing to the stage of causing blindness. Surgical removal of the lens is the only treatment that can restore vision in an animal that is blind because of cataracts. Lens luxation might also require surgical treatment. Before considering cataract surgery, veterinary ophthalmologists perform other tests to be sure the animal is a good candidate for surgery and doesn’t have other eye problems that might impair vision. Reference 1. Gelatt KN, Mackay EO. Prevalence of primary breed-related cataracts in the dog in North America. Vet Ophthalmol. 2005;8(2):101-11. doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2005.00352.x Photo by Ezequiel Garrido on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Zoë Gayah Jonker Photo by Zoë Gayah Jonker Constipation in a cat should never be ignored. Most cases of constipation are mild and last only a day or two. But cats with long-term or repeated bouts of constipation are at risk for more serious medical problems. Constipation is the infrequent or difficult passing of feces. Because the colon removes water from intestinal contents, feces that stays in the colon becomes hard and dry. In time, as more feces accumulates in the colon, the mass of hard feces gets too large to pass through the pelvic opening. This more severe form of constipation, when feces can’t pass at all, is called obstipation. A cat with obstipation has to be treated in the hospital to get the impacted feces out of the colon. Some cats with chronic (long-term) constipation and obstipation develop megacolon, a distended colon that no longer works properly. The colon wall becomes stretched and limp, so it can’t push feces toward the anus. Treatments that help relieve constipation don’t work as well for megacolon, so cats with megacolon might need surgery. Some of the many causes of constipation are medical disorders, medication side effects, obstruction of the colon (for example, by tumors or pelvic fractures), and ingested foreign material. Dehydration makes constipation worse. Cats that avoid the litter box because of orthopedic pain or stress—conflict with another cat, change of routine, illness, and so forth—can develop constipation. Megacolon can be caused by abnormal nerve control of the colon muscles (something the cat is born with). Symptoms A cat that is squatting and straining in the litter box might or might not be constipated. Male cats with urinary blockage, which is a medical emergency, also squat and strain. Animals with diarrhea have an increased urge to defecate but might pass only a little bit of liquid stool. Urinary blockage, diarrhea, and constipation can all result in a cat squatting in the litter box, looking uncomfortable, and not producing much of anything. The symptoms of constipation depend on the duration and cause and whether it has progressed to obstipation and megacolon:

Diagnosis A large amount of feces in the colon can be found with physical examination or radiographs (x-ray images). Other diagnostic tests are used to find the cause of constipation and assess the overall health of the patient. Megacolon is diagnosed with radiographs. Treatment Chronic constipation tends to become less responsive to treatment over time. The type of treatment depends on the cause and severity of constipation. Treatments for constipation include increased hydration, laxatives, medications to increase intestinal movement, enemas, and a modified diet (which could be a high-fiber diet or a low-residue diet depending on the individual case). Never give a cat a laxative or enema unless your veterinarian has specifically recommended it; some human products aren’t safe for cats. For cats with obstipation, the impacted feces must be removed in the hospital. One method is to remove the feces manually while the cat is under anesthesia. A newer method involves placing a tube through the nose into the stomach (cats tolerate this surprisingly well) and infusing a solution over several hours to break down the mass of feces so it can pass. Megacolon is managed at first with the same treatments used for constipation. If those treatments no longer work, megacolon can be treated by surgical removal of the colon. Most cats do well after this surgery. Photo by Zoë Gayah Jonker on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Tereza Hošková Photo by Tereza Hošková Cancer is most common in older animals but can develop in animals of any age. Cancer can affect almost any part of the body, so the symptoms vary. The earlier cancer is found, the better for the pet. Lumps Lumps and bumps on or under the skin are usually benign, but some are malignant (cancerous). Any lump that’s the size of a pea or larger and present for at least a month, or one that’s rapidly enlarging or changing in appearance, should be checked by a veterinarian. It’s not possible to tell if a lump is cancerous just by the way it feels. Diagnosis usually requires analyzing a sample of the lump under a microscope (see Skin Lumps in Dogs and Cats for more information). Changes in Weight Unexplained or sudden weight loss is a cause for concern. Many diseases, including cancer, can cause weight loss. Unexpected weight gain could also be a sign of cancer if it’s caused by fluid buildup. Decreased Energy Playing less, sleeping more, and moving more slowly could be effects of aging but might be caused by pain or an illness like cancer. Don’t assume that pets (especially seniors) that are slowing down or sleeping a lot are just old or tired; have a veterinarian examine them. Changes in Appetite Cancer often causes a drop in appetite. Reluctance to eat could also be caused by dental disease or other medical problems. Vomiting or Diarrhea Digestive trouble like vomiting and diarrhea is very common in dogs and cats. Vomiting or diarrhea that lasts longer than a few days and doesn’t get better with treatment—especially if the animal also has other symptoms—should be investigated further. Cancer of the digestive tract and many other medical problems can cause long-term vomiting or diarrhea. Signs of Pain Limping, reluctance to move, hunched posture, and other signs of pain could indicate cancer. Bone cancer doesn’t only affect older animals; sometimes it happens in young dogs. Contact your veterinarian if your pet has signs of pain, and never give human pain medication to an animal unless your veterinarian has specifically recommended it. Some human pain medications are toxic to dogs and cats. Coughing or Trouble Breathing Cancer of structures in the chest (lymph nodes, lungs, or heart) and cancer that has spread to the lungs are among the many causes of coughing. Swollen Belly Cancer can cause the belly to swell from fluid buildup, bleeding into the abdomen, or enlargement of abdominal organs like the liver and spleen. Changes in Urine or Stool Changes in urine volume or frequency, blood in the urine or stool, and difficulty passing urine or stool can all potentially be caused by cancer and warrant a veterinary examination. Blood in the stool looks tarry black or bright red depending on the part of the digestive tract it’s from. An inability to pass urine is a medical emergency. Discharge or Drainage Anything oozing or leaking from your pet should be checked by a veterinarian. Cancer is one of the possible causes of unusual discharge from body orifices such as the eyes, nose, mouth, and anus. Foul or Unusual Odor Bad breath is usually caused by dental or periodontal disease but could be a sign of cancer. Cancers inside the mouth and nose can be very hard to see in an animal without sedation. Tumors in other areas of the body can also cause odd odors. Wounds That Don’t Heal A skin sore or wound that doesn’t heal on its own could be a sign of skin disease, infection, or skin cancer. Photo by Tereza Hošková on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Photo by Raghavendra V. Konkathi Photo by Raghavendra V. Konkathi Vaccines for dogs and cats are safe, especially compared with the risk of disease. Most animals don’t have any untoward symptoms after receiving a vaccine. But vaccines, like any other medicine, can have some side effects. Vaccination produces an immune response, and inflammation is part of the immune response. Most of the symptoms (if any) that animals have after vaccination are caused by normal inflammation, meaning that the immune system is acting the way it’s supposed to act when it’s stimulated. Allergic (hypersensitivity) reactions to vaccines are uncommon in dogs and cats but can be serious. These reactions are caused by an inappropriate immune response. The most severe type of hypersensitivity reaction is anaphylaxis, which can be life threatening. In one study of dogs in the United States, the rate of vaccine-associated adverse events, including everything from normal inflammatory responses to anaphylaxis, was 0.38% (38 events per 10,000 vaccine doses). Anaphylaxis accounted for 1.7% of the adverse events. The risk of adverse events was highest in small-breed dogs and dogs who received multiple vaccines at the same time.[1] Mild Symptoms These are some of the common mild vaccine effects you might notice in your dog or cat. In most cases it’s safe to monitor these symptoms at home. If any of these symptoms last longer than a day or if your pet seems very uncomfortable, contact your veterinarian.

More Serious Symptoms Allergic reactions to vaccines appear minutes or several hours after vaccination. Anaphylaxis can start with these symptoms and is a medical emergency. Seek veterinary care right away if your pet has any of these symptoms.

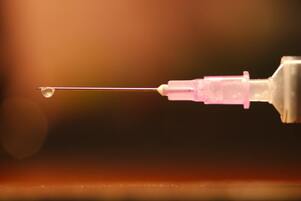

Lumps at Injection Sites Most small, firm lumps at vaccine injection sites are caused by inflammation and resolve in a couple of weeks without treatment. An injection-site lump or swelling that is still present after 3 weeks or is enlarging should be checked by a veterinarian. Injection-site cancer is rare but can happen in cats (vaccine protocols and formulations for cats minimize this risk as much as possible). Autoimmune Disease? Vaccines could—at least in theory—be linked to autoimmune diseases, in which the immune system targets cells of the body. Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (affecting red blood cells) and thrombocytopenia (affecting platelets) occur in animals, but the association of these disorders with vaccination isn’t clear.[2] The presence of an autoimmune disease would affect future vaccination decisions for the animal, though. If Your Pet Has Had a Vaccine Reaction Tell your veterinarian if your pet has had any vaccine-related symptoms. Your veterinarian will determine if your pet most likely had a normal inflammatory response or an allergic reaction. The decision on how to proceed with future vaccinations depends on the symptoms, the animal’s overall health, and the animal’s individual risk for vaccine-preventable diseases. Depending on the circumstances, options for future vaccinations might include dividing vaccines among several visits instead of giving multiple vaccines all at once, giving medication (like an antihistamine) before vaccination, using a different type of vaccine, or discontinuing a vaccination. Vaccine titers—levels of antibody in the blood—indicate whether an animal is likely to still be protected by earlier vaccines, so titer testing can replace vaccination in some cases.[3] Some of these options don’t apply to rabies vaccination, which is mandated by law. In North Carolina and South Carolina, as in many states, veterinarians cannot give medical exemptions for rabies vaccination, and rabies antibody titers can’t be used instead of vaccination.[4] References 1. Moore GE, Guptill LF, Ward MP, et al. Adverse events diagnosed within three days of vaccine administration in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227(7):1102-1108. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.227.1102 2. Tizard IR. Adverse consequences of vaccination. Vaccines for Veterinarians. 2021;115-130.e1. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-68299-2.00019-8 3. AAHA canine vaccination guidelines: vaccine adverse reactions. American Animal Hospital Association. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.aaha.org/aaha-guidelines/vaccination-canine-configuration/frequently-asked-questions/how-can-adverse-reactions-be-managed/ 4. Rabiesaware.org. Accessed August 27, 2021. http://www.rabiesaware.org/ Photo by Raghavendra V. Konkathi on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Photo by Anusha Barwa Photo by Anusha Barwa Most skin lumps in dogs are benign. In cats, skin masses are more likely to be malignant. It’s impossible to know if a mass is benign or malignant just by looking at it and feeling it. For diagnosis, a sample of cells from the mass must be examined under a microscope. Veterinarians use either fine-needle aspiration or biopsy to take samples from skin masses. Fine-needle aspiration is a quick technique that doesn’t require anesthesia. The veterinarian uses a syringe and needle (about the same size used for dog and cat vaccines) to remove a small sample from the mass. The sample is transferred to a microscope slide and either checked at the veterinary clinic or sent to a laboratory for a pathologist to evaluate. Biopsy is the removal of a section of a mass—or an entire mass, if it’s small—for submission to a laboratory. Biopsy requires at least local anesthesia; most patients need sedation or general anesthesia. Fine-needle aspiration doesn’t always yield enough cells for a definite diagnosis, so biopsy is necessary for some masses. So when is it okay to just watch a lump to see if it gets bigger, and when should a lump be checked by a veterinarian? Masses that fit these criteria should be evaluated by aspiration or biopsy:[1]

The advantage of evaluating masses while they’re small is that malignant skin tumors can often be cured if they’re removed early. Larger masses are harder to remove completely. Some types of skin cancer spread through the body (metastasize) over time. Benign Masses Benign masses don’t metastasize to other areas of the body or damage the tissues around the mass. Once diagnosed, they can be left alone unless they become painful or annoying to the animal (for example, if the surface becomes irritated or the mass grows large enough to interfere with movement). These are some of the most common benign skin lumps in dogs and cats:[2,3]

Malignant Masses Malignant masses are cancerous and invade the surrounding tissues or metastasize throughout the body. Some malignant skin tumors that can’t be cured with surgery can be treated with radiation or chemotherapy. Animals with skin cancer benefit from referral to a veterinary oncologist. These are some of the malignant skin tumors that affect dogs and cats:[2,3]

References 1. Ettinger S. See something, do something. Why wait? Aspirate. In: Proceedings of the NAVC Conference, Volume 30: Small Animal and Exotics. NAVC; 2016:720-722. 2. Gear R. Lumps and bumps: common skin tumors. British Small Animal Veterinary Congress 2008. Veterinary Information Network. Accessed August 3, 2021. https://www.vin.com/apputil/content/defaultadv1.aspx?id=3862939&pid=11254& 3. Five types of skin cancer in dogs. NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine. Accessed August 3, 2021. https://cvm.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/5-Types-of-Tumors.pdf Photo by Anusha Barwa on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  James Frewin via Unsplash James Frewin via Unsplash Motion sickness is common in dogs and cats and can cause significant anxiety in affected animals. The condition is usually associated with riding in a car, boat, or airplane. If your pet vomits during trips, contact your veterinarian for medical help. Causes Motion-related nausea is caused by stimulation of the vestibular system, a set of structures in the inner ear responsible for sense of balance and coordination of head and eye movements. Signals from the vestibular system are connected to the vomiting center in the brainstem. Motion sickness is probably related to sensory conflict when input from the eyes (what the animal sees) doesn’t match motion that the vestibular system detects.[1] Head movements that are jerky, inconsistent, or in the opposite direction of the body’s motion—all of which happen while riding in a vehicle—can trigger the neural signals that lead to vomiting.[2] Animals with motion sickness sometimes vomit before the vehicle is even moving because they’re anxious and scared. They’ve learned that riding in a vehicle makes them feel sick, so they develop fear of the vehicle itself, and that fear makes them vomit.[3] Anxiety that’s not related to motion sickness can also cause vomiting, so animals who are afraid of car rides for other reasons might vomit even if they don’t really have motion-related nausea. Symptoms Animals with motion sickness don’t always vomit. Some of the symptoms of nausea and anxiety are more subtle. Watch for these symptoms in dogs and cats:

Diagnosis Diagnosing motion sickness is usually pretty straightforward: vomiting that happens only in moving vehicles is motion sickness. A thorough history can help determine whether the animal has motion-related nausea, anxiety, or both. Vomiting that continues longer than the vehicle ride or is accompanied by other symptoms, like stomach pain, should be investigated further. Treatment Withholding food for a few hours before the animal travels is a good way to start but might only reduce the volume of vomit; it won’t help with anxiety. Puppies sometimes outgrow motion sickness,[1] especially if they receive positive-reinforcement training for vehicle rides. Training improves anxiety-related symptoms in some adult animals too. However, many animals need medicine to help them deal with motion sickness. Safe and very effective antinausea medicines for dogs and cats are available by prescription. A veterinarian can help decide whether a pet would benefit most from antinausea medicine, antianxiety medicine, or both. Motion sickness remedies for humans are available without a prescription, and some of these can be used in dogs and cats. However, never give your pet any motion sickness remedy without talking to your veterinarian first. Some of the products for humans have unwanted effects in animals. Many “natural” remedies are either untested or not effective in animals, and some might even be unsafe. References 1. Conder GA, Sedlacek HS, Boucher JF, Clemence RG. Efficacy and safety of maropitant, a selective neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist, in two randomized clinical trials for prevention of vomiting due to motion sickness in dogs. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31(6):528-532. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2008.00990.x 2. Graham H. Motion sickness in small animals: pathophysiology & treatment. Clinician’s Brief. June 2013. Accessed May 16, 2021. https://www.cliniciansbrief.com/article/motion-sickness-small-animals-pathophysiology-treatment 3. Coates JR. Motion sickness in animals. Merck Veterinary Manual. Updated March 2021. Accessed May 16, 2021. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/nervous-system/motion-sickness/motion-sickness-in-animals 4. Hickman MA, Cox SR, Mahabir S, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and use of the novel NK-1 receptor antagonist maropitant (Cerenia) for the prevention of emesis and motion sickness in cats. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31(3):220-229. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2885.2008.00952.x Image source: James Frewin via Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Pancreatitis, or inflammation of the pancreas, is common in dogs and cats. Although some cases are relatively mild, pancreatitis is painful and can cause severe disease and even death. Pancreatitis can be triggered by eating a high-fat meal or table scraps, so be very cautious about sharing holiday food with your pets. Pancreatitis is categorized as acute (a short course of disease that can be reversed) or chronic (long-term disease caused by permanent damage to pancreatic cells). These categories can overlap. Animals with repeated episodes of acute pancreatitis can develop chronic pancreatitis, and animals with chronic pancreatitis can have flares of acute disease. In cats, the chronic form is more common than the acute form.[1] The pancreas, which is located near the stomach and small intestine, produces digestive enzymes and insulin. Because of the anatomic location and functions of the pancreas, pancreatic disease doesn’t always happen in isolation. Diseases of the liver, bile duct, and small intestine affect the pancreas and vice versa. In cats, simultaneous inflammation of the liver, small intestine, and pancreas is called triaditis.[2] Chronic pancreatitis is associated with diabetes mellitus and deficiency of digestive enzymes. Causes The cause of pancreatitis in dogs and cats is often not found. However, some risk factors make pancreatitis more likely:

Symptoms The symptoms of pancreatitis vary according to disease severity and are not specific; many disorders can cause the same symptoms. Symptoms are usually more severe with acute pancreatitis than with chronic pancreatitis. Other disorders that accompany pancreatitis also contribute to the symptoms. These are some of the symptoms of acute pancreatitis:

The symptoms of chronic pancreatitis are often vague and can be mistaken for other disorders. Animals with chronic pancreatitis might have these symptoms:

Diagnosis Diagnosing pancreatitis can be tricky, especially in animals with vague symptoms or multiple organ systems affected. Baseline bloodwork and urinalysis don’t necessarily give a diagnosis but help assess the patient’s overall health and reveal associated disorders. A diagnosis of pancreatitis is typically made with a combination of blood tests for pancreas-specific factors (like serum amylase, serum lipase, canine and feline pancreas-specific lipase, pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, and trypsin-like immunoreactivity) and ultrasonography of the abdomen.[4] Treatment Animals with acute pancreatitis usually need to stay in the hospital for at least a few days. Treatment can include intravenous fluids, pain management, antiemetics to control vomiting, tube feeding, possibly antibiotics, treatment of the underlying cause (if known), and treatment of associated disorders. Patients are monitored closely for complications like organ failure and blood clotting disorders. Animals with recurrent acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, or triaditis might need long-term diet modification.[2,5] Prognosis The prognosis depends on disease severity. Patients with mild disease tend to recover well, but the prognosis is guarded for animals with severe pancreatitis. References 1. Watson P. Pancreatitis in dogs and cats: definitions and pathophysiology. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56(1):3-12. doi:10.1111/jsap.12293 2. Simpson KW. Pancreatitis and triaditis in cats: causes and treatment. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56(1):40-49. doi:10.1111/jsap.12313 3. Lem KY, Fosgate GT, Norby B, Steiner JM. Associations between dietary factors and pancreatitis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233(9):1425-1431. doi:10.2460/javma.233.9.1425 4. Xenoulis PG. Diagnosis of pancreatitis in dogs and cats. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56(1):13-26. doi:10.1111/jsap.12274 5. Steiner JM. Pancreatitis in dogs and cats. Merck Veterinary Manual. Updated October 2020. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/digestive-system/the-exocrine-pancreas/pancreatitis-in-dogs-and-cats Photo by Sebastian Coman Travel Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Diabetes mellitus is an endocrine disorder that leads to high levels of glucose (a type of sugar) in the blood. Diabetes is common in dogs and cats. November is Pet Diabetes Month, so this article is a brief overview of this complex disorder. Causes Carbohydrates in the diet are converted to glucose in the body. The hormone insulin helps move glucose from the bloodstream into cells, where glucose is a source of energy. Diabetes mellitus occurs either when the body doesn’t produce enough insulin or when the body can’t use insulin properly. Insulin is made in the pancreas. Immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic cells or pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) can reduce insulin production. Dogs and cats can also develop insulin resistance, in which the pancreas makes insulin but the body doesn’t respond normally to it.[1] This type of diabetes, similar to type 2 diabetes in people, is the most common type in cats.[2] Risk Factors Obesity is a major risk factor for diabetes in dogs and cats. Obese cats are up to 4 times as likely as cats of ideal weight to develop diabetes.[2] Other diseases, like hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing disease) and hypothyroidism in dogs, acromegaly in cats, dental disease, and kidney disease, are also associated with diabetes. Some medications, especially glucocorticoids like prednisone, increase the risk for diabetes. Breeds that are more prone than others to diabetes include beagles, Australian terriers, Samoyeds, keeshonds, and Burmese cats.[1] Symptoms In animals with a high blood glucose level, excess glucose is excreted in the urine. Glucose in the urine acts as a diuretic, increasing urine volume. Animals with diabetes often develop urinary tract infections because of the sugar in the urine. When cells can’t use glucose properly for fuel, the body begins to break down fat and muscle. These changes in metabolism affect many organ systems. Uncontrolled diabetes can also lead to diabetic ketoacidosis, a potentially life-threatening complication. These are some of the symptoms of diabetes:

Diagnosis Diabetes is diagnosed by blood and urine tests showing high glucose levels that persist on repeat testing. In cats, stress can increase the blood glucose level, so measurement of serum fructosamine (a protein that reflects average blood glucose levels over the previous week or so) can help with diagnosis. Full bloodwork, urinalysis, and urine culture are done to identify other conditions that might accompany or result from diabetes and complicate treatment. Treatment Dogs and cats with diabetes are treated with insulin injections and diet modification. Oral medications for diabetes don’t work for dogs and aren’t very effective in cats, so all dogs and almost all cats with diabetes require insulin injections.[1] The type and dose of insulin and the diet chosen depend on the individual patient and can change over time. Other disorders can affect the body’s response to insulin and must also be identified and treated. Sick patients with ketoacidosis need intensive treatment in the hospital. Treating diabetes requires significant pet owner commitment and regular monitoring. The injections must be given on a consistent schedule, and owners need to monitor their pet’s appetite and watch for signs of hypoglycemia (low blood glucose): sleepiness, weakness, stumbling, tremors, and seizures. In dogs and cats, blood glucose is monitored from time to time with a glucose curve, a series of glucose measurements over the course of a day, either at home or at the veterinary clinic. Insulin dose adjustments are generally based on glucose curve results, not on single spot checks of blood glucose. Prognosis In dogs, diabetes almost always requires lifelong insulin therapy. Some cats treated for diabetes undergo remission and no longer need insulin, especially if their blood glucose levels can be brought under control with insulin and diet early in the course of disease.[1] The prognosis is generally good for dogs and cats with well-controlled diabetes. References 1. Behrend E, Holford A, Lathan P, Rucinsky R, Schulman R. 2018 AAHA diabetes management guidelines for dogs and cats. American Animal Hospital Association. 2018. Accessed November 20, 2020. https://www.aaha.org/globalassets/02-guidelines/diabetes/diabetes-guidelines_final.pdf 2. Sparkes AH, Cannon M, Church D, et al; ISFM. ISFM consensus guidelines on the practical management of diabetes mellitus in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17(3):235-250. doi:10.1177/1098612X15571880 Photo by Mustang Joe Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  If your pet’s eye is red, have it checked by a veterinarian without delay. Eye redness is a nonspecific symptom. It’s nearly always impossible to tell whether a red eye is minor or serious without ophthalmic tests at a veterinary clinic. These are some of the conditions that cause red eyes in dogs and cats. Conjunctivitis Conjunctivitis, called pinkeye in people, is inflammation of the tissue that lines the eyelids and covers the whites of the eyes. Causes of conjunctivitis in pets include environmental irritants, allergies, skin disease, dry eye, and (especially in cats) viral or bacterial infections. Some of the conditions that cause conjunctivitis also affect the eyelids and the cornea, the clear front part of the eye. Corneal Ulcer Corneal ulcers are defects on the surface of the cornea. In dogs and cats they can be caused by things poking the eye (like turned-in eyelashes, a foreign object under the eyelid, or being swatted in the face by a cat), infections, dry eye, disorders of corneal cells, and chronic eye exposure in flat-faced animals with shallow eye sockets. Corneal ulcers and scratches are painful. Some ulcers are shallow and heal fairly quickly with treatment. Others are deep and can perforate all the way through to the interior of the eye. Diagnosis requires applying an ophthalmic stain to highlight the corneal defect. Trauma Trauma to the outer surface of the eye causes redness of the white part of the eye, similar to the redness caused by conjunctivitis. Blunt trauma to the head can cause bleeding inside the eye, which looks like dark red discoloration behind the cornea. Bleeding disorders and other conditions can also cause blood accumulation inside the eye. Uveitis Uveitis is inflammation of the interior of the eye. Uveitis doesn’t happen on its own; it’s a sign of another problem. Some of the diseases that cause uveitis affect the whole body: infections, tick-borne diseases, immune-mediated disorders, cancer, and so forth. Uveitis is also caused by eye disorders like cataracts. Uveitis is a painful condition that can lead to glaucoma. Diagnosis involves examination of the eye, measurement of eye pressure, and tests to find the underlying cause. Glaucoma Glaucoma is a disease characterized by increased pressure within the eye. The condition is inherited in some dog breeds and is also caused by uveitis, lens luxation (lens slipping out of place), and cancer of the eye. Glaucoma is painful and leads to blindness. Sudden-onset glaucoma is a medical emergency if vision is to be saved. Cherry Eye Cherry eye is the common term for prolapse of the gland of the nictitating membrane, a pink membrane (sometimes with a dark edge) at the inner corner of the eye. A tear gland within this membrane can swell and protrude past the edge. The prolapsed gland looks like a round pink or red mass at the inside corner of the eye. This is the one type of “red eye” that doesn’t require an immediate visit to the veterinarian—unless other symptoms, like squinting or eye discharge, are also present. However, a prolapsed tear gland can cause eye irritation, and tumors in this area look similar, so it should still be checked out. Prolapsed tear glands are treated surgically. Photo by Céline Harrand |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Christmas Party 2023

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed