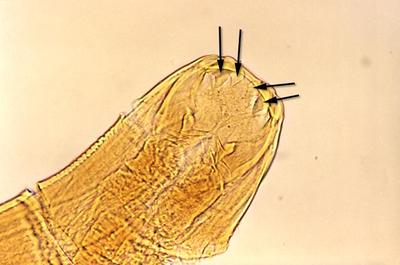

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Hookworms are common in dogs and cats, especially young animals in warm climates. These parasites are also zoonotic: hookworms that infect dogs and cats can also infect people. What are hookworms? Hookworms are small parasitic worms that live in the intestines of host animals. Different hookworm species have different preferred hosts. Hookworm larvae can also infect other animals—accidental hosts—that they happen to come in contact with. The symptoms of infection depend on whether the infected animal is a preferred host or an accidental host. Adult hookworms in the intestines lay eggs that are passed out of the body through feces. Once in the environment, the eggs hatch into larvae. Larvae enter a new host’s body by penetrating the skin. Preferred hosts can also be infected by swallowing hookworm larvae, such as by eating contaminated dirt. Puppies can be infected through their mother’s milk. In preferred hosts, hookworm larvae migrate to the intestines, where they grow into adult worms that reproduce and lay eggs. In accidental hosts, hookworm larvae cause a local reaction where they have penetrated the skin, but they do not mature and reproduce. Hookworm infection in dogs and cats The hookworm species that most often infect dogs and cats are Ancylostoma caninum, Uncinaria stenocephala, Ancylostoma tubaeforme, and Ancylostoma braziliense. These worms attach to the lining of the intestines and feed on blood. Infection can cause anemia from blood loss, which can be fatal in young puppies and kittens carrying large numbers of worms. Symptoms of hookworm infection in dogs and cats depend on the number of worms and the age, size, and overall health of the infected animal.

A number of effective, safe medications are available to treat hookworm infections in dogs and cats. Young animals with severe anemia may need blood transfusions. Hookworm infection in people Humans can be infected by dog and cat hookworms if they come in contact with larvae in the environment—for example, by walking barefoot on sand or soil contaminated with hookworm larvae. The larvae burrow into the skin, causing an itchy skin reaction called cutaneous larva migrans. The larvae live only a few weeks in humans, so the symptoms may resolve on their own (contact your health care provider if you have more questions). Humans are the preferred hosts for 2 hookworm species: Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. These hookworms are a major source of human disease worldwide and were once common in the southeastern United States. Preventing hookworms Because dog and cat hookworms cause serious disease in animals and are also a health risk for people, preventing hookworm infections in our pets is important for both animal and human health. The Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends the following for dogs and cats:

The CDC recommends these steps to prevent zoonotic hookworm infections in people:

For more information Hookworms (PDF from Worms & Germs Blog) Hookworms – Dog Owners and Cat Owners (Companion Animal Parasite Council) Zoonotic hookworm FAQs (CDC) Photo by Andrew Pons Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Preventive health care helps pets live longer, happier lives. But some cats are so anxious about travel that bringing them to the clinic—not to mention examining and treating them—is a challenge. Resistance to carriers and stress at the veterinary hospital are two of the top reasons that some cats receive no preventive health care at all. Here are some things you can do at home to make trips to the clinic easier for your cat. Choosing a carrier Choose a carrier that is easy to get your cat into and out of. Lifting a cat out of a top opening is less stressful (to the cat) than pulling or dumping her out of a front opening. A front-loading carrier lets a cat walk in on her own, so consider carriers with both front and top doors. Rigid plastic carriers that come apart in the middle are great for cats who are anxious at the clinic. Taking the top half of the carrier off makes it easy to gently scoop out a cat. Sometimes the cat can stay in the bottom half, where she might feel more secure, for most of the examination. Getting your cat used to the carrier Cats need lots of time to adjust to new things. Let your cat get used to the carrier at home before you need to bring her to the clinic.

Once your cat is going into the carrier on her own, shut the door for brief periods. Continue to give positive reinforcement: occasionally drop a treat through the top while the door is shut. Let her out before she shows signs of anxiety (ears pinned back, flattened or frozen posture, vocalization). Getting your cat used to traveling After your cat has accepted the carrier as a normal part of life, take her on short car rides that end in something fun. Dogs who love car rides have learned that good things happen after a trip. Cats are often put in the car only to go somewhere they don’t like, so naturally they are less happy about it. Try taking very short trips that end at home, with treats and toys when you get back. Medication Carrier training and synthetic feline pheromones are just not enough to manage some cats’ fears. (Cats who are aggressive at the clinic are scared cats, not bad cats.) Or you might need to bring your cat to the clinic before you have time to accustom her to the carrier. Antianxiety medication given at home before a clinic visit can make a big difference for some cats. Call the clinic if you’d like to discuss the options. We want the clinic experience to be as stress-free as possible for both you and your cat. More information from the American Association of Feline Practitioners Choosing the perfect cat carrier Cat carrier tips Getting your cat to the veterinarian Photo by Paul |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed