Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Haley Owens Photo by Haley Owens Socializing young kittens and puppies means giving them positive experiences with things they’ll encounter throughout their lives. Building positive associations early in life helps animals feel comfortable with new people and new situations. Animals that are well socialized when they’re young are less likely to develop fear-based behavior problems (like aggression) that could put them at risk of being sent to a shelter or euthanized later on. Sensitive Period for Socialization For kittens, the window of opportunity for socialization is very early: from 3 weeks to about 7 to 9 weeks of age.[1,2] The sensitive period is the time when a young kitten’s brain is most receptive to socialization. During these early weeks, a kitten is exploring and learning, developing neurological pathways that will help the kitten learn in the future. After the sensitive period, brain development shifts; kittens don’t make positive associations as quickly or easily and they’re more likely to be afraid of new things. This is why it’s so difficult, if not impossible, to convert a semi-feral adult cat into a cat that can be happy living as a house pet. You will have noticed that the sensitive socialization period for kittens is nearly closed by the time they’re typically adopted or purchased. Socialization needs to start with the person caring for the mother cat and newborns. When you adopt or buy a kitten, continue providing socialization (at the kitten’s comfort level and pace) to reinforce what the kitten has already learned. The socialization process should always be positive. Don’t force kittens to interact with strangers or other animals if they’re shy, and don’t push them to be near things that scare them. Let them choose whether to interact. Give them room to walk away and let them hide if they want to. Use positive reinforcement (food or play) to encourage them to interact and build their confidence. The following suggestions are adapted from the American Veterinary Medical Association.[1] For more tips, check out the First Year of Life page on the Cat Friendly Homes website: https://catfriendly.com/life-stages/first-year-life/ Socializing Kittens Before Weaning

Socializing Kittens 8 to 12 Weeks Old

Older Kittens and Newly Adopted Adult Cats

References 1. Welfare implications of socialization of puppies and kittens. American Veterinary Medical Association. June 9, 2015. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/literature-reviews/welfare-implications-socialization-puppies-and-kittens 2. Todd Z. The sensitive period for socialization in puppies and kittens. Companion Animal Psychology. July 26, 2017. Accessed July 8, 2022. https://www.companionanimalpsychology.com/2017/07/the-sensitive-period-for-socialization.html Photo by Haley Owens on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Whipworms are intestinal parasites that are relatively common in dogs and can cause serious illness. Some (not all) monthly heartworm preventives prevent whipworm infection. Canine whipworms are small worms about 2 to 3 inches long that live in the cecum, a pouchlike structure attached to the large intestine. The whipworm that infects dogs, Trichuris vulpis, does not infect humans. (Another species of whipworm can infect people.) Whipworms are very rare in cats in North America. According to the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC), almost 50,000 dogs in the United States tested positive for whipworms in 2019. About 2500 of these dogs were in North Carolina, putting North Carolina in the CAPC high-risk category for whipworms.[1] Transmission Dogs are infected with whipworms when they swallow whipworm eggs in the environment—for example, by licking dirt from their feet.[2] The eggs hatch in the dog’s intestines and grow to adult worms in the cecum. About 2.5 to 3 months after the dog is infected, the adult worms begin producing eggs that pass out of the body in the feces. Whipworm eggs in the environment take about 2 to 3 weeks (or longer) to develop into a stage that can infect dogs. This means that dogs are infected by swallowing contaminated substances, not by eating fresh dog poop. Whipworm eggs in the environment are resistant to temperature changes and sunlight and are able to infect dogs for years.[3] Symptoms Symptoms of whipworm infection depend partly on the number of worms present and can include the following:

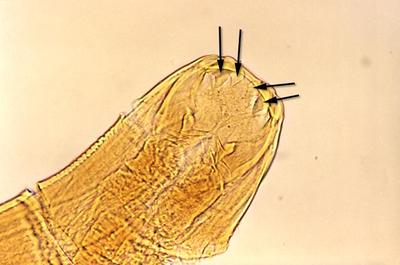

Diagnosis Whipworm infection can be a little tricky to diagnose. Typical fecal analysis at a veterinary clinic involves looking for worm eggs in a stool sample under a microscope. However, because whipworms don’t produce eggs for the first few months after infection and they don’t produce eggs all of the time, stool analysis with a microscope can miss the infection. Sending a fecal sample to a diagnostic laboratory for a whipworm antigen test can increase the chance of finding the infection. Treatment and Prevention Antiparasitic drugs to treat whipworm infection are typically given in at least 2 doses spaced a few weeks apart. Monthly heartworm preventives that contain milbemycin (given by mouth) or moxidectin (applied to the skin) will treat and prevent whipworm infection.[3] Other heartworm preventives available at the time of writing (May 2020) are not effective against whipworms. It’s not possible to completely eliminate whipworm eggs that are already in the environment. The CAPC recommends reducing dogs’ risk by removing dog feces from the environment and regularly testing dogs for whipworms. References 1. Parasite prevalence map: 2019, whipworm, dog, United States. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://capcvet.org/maps/#2019/all/whipworm/dog/united-states/ 2. Brooks W. Whipworm infection in dogs and cats. Veterinary Partner. Published May 8, 2004. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/doc/?id=4952061&pid=19239 3. Trichuris vulpis. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Updated October 1, 2016. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/trichuris-vulpis/ Image: photomicrograph of Trichuris vulpis egg, 400× magnification. Credit: CDC/Dr Mae Melvin. Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Roundworms are some of the most common internal parasites in dogs and cats. They can also infect humans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 13.9% of people in the United States have antibodies to roundworms, meaning they have been exposed to the parasite at some point in their lives. How dogs and cats are infected Almost all puppies are born with roundworms. The type of roundworm that most often infects dogs, Toxocara canis, transfers from a mother dog to unborn pups through the placenta. T canis can also pass to puppies through the mother’s milk. Infected animals excrete roundworm eggs in their stool, so dogs can be infected by eating feces or swallowing roundworm eggs in the environment. Dogs can also become infected by eating a small animal (like a rodent) that is carrying roundworms. The most common roundworm in cats is Toxocara cati. Cats and kittens are usually infected by swallowing roundworm eggs in the environment or by eating an infected animal. T cati does not pass to unborn kittens through the mother’s placenta. Ingested T canis and T cati eggs hatch into larvae in the intestines. The larvae migrate through body tissues to the lungs, are coughed up and swallowed, grow into adult worms in the intestines, and begin producing eggs that pass into the environment through the feces. Roundworm larvae can remain dormant in body tissues of adult animals instead of maturing in the intestines. These arrested-development larvae can’t be detected by fecal tests for worm eggs because they don’t produce eggs. Dormant larvae in a pregnant dog can become active and move through the placenta to the pups. In other words, a female dog with a negative test for roundworms can pass roundworms to her puppies anyway. Signs of infection Infected animals often have no symptoms at all. Dogs and cats (especially puppies and kittens) with lots of roundworms may develop a potbelly, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, or dull coat. Heavily infected animals sometimes vomit worms, which look a bit like spaghetti noodles, or pass worms in the stool. Treatment and prevention in pets Young puppies and kittens should receive multiple doses of deworming medication. The Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends deworming puppies and kittens every 2 weeks starting at age 2 weeks for pups and 3 weeks for kittens, continuing until they are about 2 months old, and then beginning monthly parasite preventives. Many heartworm preventives also prevent roundworm infection. To reduce the chance your pets will be infected, remove feces from the environment and try to keep them from eating rodents or other wild animals. Have your veterinarian regularly test your pets for parasites, and give them parasite preventives all year round. Infection in humans People can be infected by T canis or T cati if they ingest contaminated dirt or feces. Toxocara eggs can survive in the soil for years. Children and people who own dogs or cats have an increased risk of infection, says the CDC. Many people with Toxocara infection don’t develop serious disease and have no symptoms. But T canis and T cati larvae can migrate through the bodies of humans, as they do in dogs and cats. Larvae that migrate to internal organs (such as the liver) damage these tissues, a disease process called visceral larval migrans or visceral toxocariasis. Symptoms depend on the organs affected. Sometimes larvae migrate to the eye, causing a disease known as ocular larval migrans or ocular toxocariasis. People with this condition may develop retinal inflammation and vision loss. Prevention in humans The CDC recommends these steps to prevent toxocariasis:

For more information Ascarid (Companion Animal Parasite Council) Cat Owners: Roundworms and Dog Owners: Roundworms (Pets and Parasites) Toxocariasis FAQs (CDC) Photo by Berkay Gumustekin Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Both indoor and outdoor cats need vaccines. Vaccination protects cats against infectious diseases that cause serious illness or death. This article describes the vaccines that veterinarians commonly recommend for cats. One factor that affects vaccination protocols for cats—but not dogs—is the risk of injection-site sarcomas. Some cats develop these malignant tumors at the injection sites of vaccines or other substances. These cancers are uncommon (estimated to occur in 1 to 10 of every 10,000 cats vaccinated) but can be devastating. Although the vast majority of cats do not develop injection-site sarcomas, feline vaccination protocols are designed to balance the tumor risk with the need to keep cats protected from infectious disease. Recommendations include giving cats only the vaccines that are necessary, vaccinating cats no more often than necessary, and using vaccine formulations that are less likely to cause sarcomas. Rabies virus Rabies vaccination is mandated by law for dogs and cats in the United States. In North Carolina, all cats, dogs, and ferrets aged 16 weeks and older must be vaccinated against rabies. Rabies vaccination laws are one reason this fatal disease is very rare in humans in the United States. Around the world, rabies kills tens of thousands of people every year. Cats in North Carolina can and do get rabies. In 2017, cats were 1 of the 5 most common species to test positive for rabies in this state (after raccoons, skunks, foxes, and bats). The total number is low, but the risk is real. Cats that live 100% indoors need rabies vaccines too. Cats sometimes escape outside. And sometimes the unexpected happens, like a bat getting into the house. The presence of a bat indoors is considered a rabies exposure unless the bat is caught and tests negative. A cat that is exposed to rabies but does not have a current rabies vaccination is subject to quarantine for up to 6 months. Also, a cat that bites a person must be quarantined for 10 days; cats without current rabies vaccinations typically spend this quarantine at a facility instead of at home. For more information, see the post about NC rabies laws. In North Carolina, the first rabies vaccine a cat receives lasts for 1 year, and subsequent vaccines can legally be given every 3 years (as long as the vaccine is labeled for 3-year use). If your veterinarian recommends giving your cat a rabies vaccine every year instead of every 3 years, it’s probably because the clinic uses a feline rabies vaccine that is designed to reduce the sarcoma risk and is labeled for 1-year use. Most 3-year rabies vaccines on the market are killed-virus vaccines that contain adjuvants, substances that enhance the immune response. Killed, adjuvanted rabies vaccines have been associated with injection-site sarcomas in cats. A different type of rabies vaccine, a recombinant vaccine, does not contain adjuvants. The most common version of the recombinant rabies vaccine is a 1-year vaccine. Ask your veterinarian which type of rabies vaccine the clinic uses for cats. Feline herpesvirus 1 (rhinotracheitis), calicivirus, and panleukopenia virus Vaccines for feline herpesvirus 1, calicivirus, and panleukopenia virus are often included in a single combination vaccine. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) recommends that all cats be vaccinated against these viruses as kittens (in a series of boosters), again 1 year later, and then every 3 years. In past decades, cats received these vaccines every year, but annual vaccination is no longer considered necessary. Feline herpesvirus 1 and calicivirus are 2 of the main causes of feline respiratory disease complex. This illness spreads easily from cat to cat. People can also carry the infectious agents on their clothing, which is how indoor cats can be infected. Infection causes sneezing, discharge from the nose and eyes, conjunctivitis (pinkeye), fever, mouth ulcers, and eye ulcers. Some combination vaccines also cover Chlamydophila (Chlamydia) bacteria, which cause conjunctivitis in cats. Feline panleukopenia virus is very contagious among cats, and infection can be fatal. The virus is similar to canine parvovirus. Like parvovirus, it destroys cells lining the intestine and impairs immune function. In kittens, it can also damage the part of the brain that regulates coordination and balance. Feline leukemia virus Feline leukemia virus is a retrovirus that suppresses immune function and causes cancer. Because the virus impairs immunity, infected cats develop a wide variety of medical problems. Most infected cats die within 3 years of diagnosis. There is currently no cure. Vaccines against feline leukemia virus have been associated with injection-site sarcomas. For this reason, the decision to vaccinate an adult cat usually depends on the cat’s lifestyle and risk factors. However, the AAFP recommends vaccinating all kittens against feline leukemia virus. A nonadjuvanted recombinant vaccine is available. Photo by Sticker Mule on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Dogs often receive vaccines during their veterinary wellness visits. But what are all of those shots for? This article describes the diseases that canine vaccines help prevent. Vaccines save lives and are safe, but your dog might not need every vaccine available. Vaccination is a medical procedure, and the choice of vaccines to use is specific to each dog. Talk to your veterinarian about your dog’s risk factors. The American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) lifestyle-based vaccine calculator is a good starting point. Canine vaccines fall into 2 categories: core vaccines, which are recommended for all dogs, and noncore vaccines, which are recommended for dogs whose lifestyle and environment put them at risk of infection. Core vaccines Rabies Rabies vaccination is mandated by law in the United States. In North Carolina, all dogs, cats, and ferrets older than 4 months must be vaccinated against rabies. Rabies is caused by a virus that is spread through the saliva of infected mammals. After an incubation period that can last up to several months, the virus attacks the brain. Infection is almost always fatal once symptoms begin. The rabies vaccine is an example of an animal vaccine that also protects human health. Read more about rabies in the blog post about NC rabies laws. Canine distemper virus, canine adenovirus 2, and parvovirus Vaccines against canine distemper virus, adenovirus 2, and parvovirus are included in a single combination vaccine. Canine distemper virus infection causes fever and respiratory symptoms (runny nose and coughing) before it proceeds to the nervous system, resulting in seizures and possibly death. Dogs that survive the initial infection can have nervous system abnormalities for the rest of their lives. Canine adenovirus 1 causes infectious canine hepatitis, a potentially fatal liver disease that also affects blood clotting ability. The vaccine against adenovirus 1 can have unwanted effects, so the currently recommended vaccine targets canine adenovirus 2, a variant that causes respiratory illness. The adenovirus 2 vaccine protects against both virus variants. Canine parvovirus is a highly contagious, sometimes fatal infection spread through the feces of infected animals. Puppies and incompletely vaccinated dogs are most likely to be infected. Parvovirus causes severe intestinal disease (diarrhea and vomiting) and disrupts immune function. Antibody tests (vaccine titers) are available for canine distemper virus, adenovirus 2, and parvovirus and may be an alternative to vaccination for some dogs. Noncore vaccines Bordetella bronchiseptica and canine parainfluenza virus Infectious tracheobronchitis, or kennel cough, is a highly contagious respiratory disease caused by a variety of viruses and bacteria. Bordetella bronchiseptica (a bacterium), canine parainfluenza virus, canine distemper virus, and canine adenovirus 2 are some of the organisms that cause kennel cough. Kennel cough is usually mild, but some dogs develop more serious illness. Kennel cough vaccines target Bordetella and sometimes parainfluenza virus. Parainfluenza virus vaccine is also included in some combination distemper/parvovirus vaccines. Leptospira Leptospirosis is caused by infection with Leptospira bacteria. This infection is zoonotic: it can spread between animals and humans. Leptospira are carried by many animal species, including wildlife and farm animals, and are usually transmitted through urine. Animals become infected through any contact with infected urine, including exposure to contaminated water or soil. Leptospirosis ranges from mild illness to kidney failure, liver failure, and death. Canine influenza virus Like kennel cough, canine influenza is a very contagious respiratory illness. Most dogs develop the mild form of flu, but the disease progresses to pneumonia in some dogs and can be fatal. Two strains of influenza virus are known to cause canine flu. AAHA recommends vaccinating at-risk dogs against both strains. Borrelia burgdorferi The bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi is responsible for Lyme disease, a tick-borne disease that causes fever and lameness in many animal species, including dogs and humans. North Carolina is currently on the border of one of the geographic areas with a high risk for Lyme disease. For more information Canine vaccination guidelines (AAHA) Vaccinations (American Veterinary Medical Association) Photo by Jay Wennington Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Zoonotic diseases, or zoonoses, are infections spread from animals to people (and vice versa). Many zoonotic diseases are transmitted by insects, wildlife, and livestock, and some are carried by pets. Controlling zoonotic disease is a cornerstone of One Health, the concept that human health, animal health, and the environment are all linked. July 6 is World Zoonoses Day and is also the anniversary of the day Louis Pasteur administered the first successful rabies vaccination to a person (July 6, 1885). How to reduce your risk Preventive care for pets helps keep everyone in the family safe. The chance of contracting a zoonotic disease from a dog or cat is low if you take proper precautions. Zoonotic infections are also spread by contaminated food, insects, ticks, farm animals, birds, reptiles, and rodents. Young children, older adults, and people with compromised immune systems are at higher risk than others. These measures can lower your risk:

Find out more at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Zoonoses in companion animals Many zoonotic diseases have been identified, and the CDC estimates that 75% of emerging infectious diseases originated in animals (often insects). Some of the most common zoonotic diseases in companion animals are listed below. Bacteria

Parasites

Other infectious agents

For more information: Zoonotic diseases (CDC) Zoonotic diseases and pets FAQ (American Veterinary Medical Association) Photo by Lydia Torrey Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Hookworms are common in dogs and cats, especially young animals in warm climates. These parasites are also zoonotic: hookworms that infect dogs and cats can also infect people. What are hookworms? Hookworms are small parasitic worms that live in the intestines of host animals. Different hookworm species have different preferred hosts. Hookworm larvae can also infect other animals—accidental hosts—that they happen to come in contact with. The symptoms of infection depend on whether the infected animal is a preferred host or an accidental host. Adult hookworms in the intestines lay eggs that are passed out of the body through feces. Once in the environment, the eggs hatch into larvae. Larvae enter a new host’s body by penetrating the skin. Preferred hosts can also be infected by swallowing hookworm larvae, such as by eating contaminated dirt. Puppies can be infected through their mother’s milk. In preferred hosts, hookworm larvae migrate to the intestines, where they grow into adult worms that reproduce and lay eggs. In accidental hosts, hookworm larvae cause a local reaction where they have penetrated the skin, but they do not mature and reproduce. Hookworm infection in dogs and cats The hookworm species that most often infect dogs and cats are Ancylostoma caninum, Uncinaria stenocephala, Ancylostoma tubaeforme, and Ancylostoma braziliense. These worms attach to the lining of the intestines and feed on blood. Infection can cause anemia from blood loss, which can be fatal in young puppies and kittens carrying large numbers of worms. Symptoms of hookworm infection in dogs and cats depend on the number of worms and the age, size, and overall health of the infected animal.

A number of effective, safe medications are available to treat hookworm infections in dogs and cats. Young animals with severe anemia may need blood transfusions. Hookworm infection in people Humans can be infected by dog and cat hookworms if they come in contact with larvae in the environment—for example, by walking barefoot on sand or soil contaminated with hookworm larvae. The larvae burrow into the skin, causing an itchy skin reaction called cutaneous larva migrans. The larvae live only a few weeks in humans, so the symptoms may resolve on their own (contact your health care provider if you have more questions). Humans are the preferred hosts for 2 hookworm species: Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus. These hookworms are a major source of human disease worldwide and were once common in the southeastern United States. Preventing hookworms Because dog and cat hookworms cause serious disease in animals and are also a health risk for people, preventing hookworm infections in our pets is important for both animal and human health. The Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends the following for dogs and cats:

The CDC recommends these steps to prevent zoonotic hookworm infections in people:

For more information Hookworms (PDF from Worms & Germs Blog) Hookworms – Dog Owners and Cat Owners (Companion Animal Parasite Council) Zoonotic hookworm FAQs (CDC) Photo by Andrew Pons Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Part 1 of this 2-part series covered the reasons we have rabies laws. This article briefly summarizes North Carolina rabies regulations and describes what to do if you find a bat in the house, your pet is bitten, or your pet has had contact with a wild animal. This article includes changes to NC rabies regulations that go into effect on October 1, 2017, and recommendations from Jose Pena, epidemiology specialist with Mecklenburg County Public Health (via telephone interview). North Carolina rabies regulations 1. Dogs, cats, and ferrets over 4 months of age must be vaccinated against rabies. The earliest the vaccine can be given is 3 months (12 weeks) of age. 2. Dogs and cats receive a rabies booster vaccine 1 year after the first vaccine and every 3 years thereafter, if the vaccine is licensed for 3-year use. (Mallard Creek Animal Hospital uses a nonadjuvanted vaccine with a 1-year license for most cats.) 3. Dogs and cats are considered immunized 28 days after the first rabies vaccine. 4. If a pet bites a person, the bite must be reported to Animal Control and the pet must be quarantined for 10 days. Animal Control decides the quarantine location. Animals with a current rabies vaccination and no bite history may be quarantined at the owner's home. Animals with an expired or no rabies vaccination or (in some cases) a history of biting or scratching are quarantined at a shelter or veterinary facility. 5. All potential exposures should be reported to Animal Control. The local health director determines whether rabies exposure is likely. Exposure to rabies doesn’t necessarily mean a bite wound. Any type of contact with a wild animal, especially rabies vector species like bats, raccoons, skunks, foxes, and coyotes, can constitute exposure. Unvaccinated cats and dogs can also carry rabies. The presence of a bat in the house is usually considered exposure because bat bites are hard to see and it’s often impossible to know how long the bat has been indoors. 6. If a dog, cat, or ferret is exposed to rabies:

What you should do 1. Keep your pets’ vaccinations current. This includes indoor-only cats! 2. If your pet bites someone, don’t avoid the consequences; just accept the 10-day quarantine. 3. If a bat is in your house:

4. If your pet is bitten by an unknown animal, a wild animal, or a dog or cat with unknown vaccination status:

5. If you you notice a wild animal acting strangely or you have found a dead wild animal:

6. To avoid attracting wild animals, feed your pets indoors and don’t leave food outside. For more information Rabies control and prevention in North Carolina: NC Health and Human Services website Protect yourself from rabies: Mecklenburg Government website September 28, 2017 Photo by Inge Wallumrød Laurie Anne Walden, DVM You may have read a recent news report of a Mecklenburg County puppy quarantined for 6 months after possible exposure to a bat. Did you wonder why the quarantine was so long? This is the first of 2 posts about rabies laws in North Carolina. This article covers background information about rabies: the reasons for the laws. The second article will discuss NC rabies regulations and what they mean for your pets (preview: vaccinate your indoor cats). Why rabies vaccination is mandated by law Rabies is caused by a virus transmitted between animals and people. It is almost always fatal once symptoms begin, but it can be prevented with vaccination. Rabies kills an estimated 59,000 people worldwide every year. Nearly all of these deaths are caused by exposure to rabid domestic dogs. Most deaths occur in areas of Asia and Africa where access to vaccination is limited. Compare that statistic with the current situation in the United States. In this country rabies kills only 1 or 2 people annually, the dog variant of the rabies virus has been eliminated, and the rabies reservoir species are wild animals. Before rabies control programs were introduced, more than 100 people in the United States died from rabies each year. The conclusion is simple: rabies control programs save lives. Rabies in North Carolina Rabies is still a real risk in the United States. Thousands of wild animals (most often bats, raccoons, and skunks) test positive for rabies each year. The most commonly infected domestic animals are cats, followed by cows and dogs. In 2016, 251 animals tested positive for rabies in North Carolina. In Mecklenburg County, 19 animals tested positive, the highest number of any NC county. Nine animals tested positive in Cabarrus County. Nearly half of the rabies-positive animals in North Carolina in 2016 were raccoons. The others, in descending order, were foxes, skunks, bats, cats, cows, dogs, beavers (Mecklenburg had 1 of the 2 rabid beavers in the state), and a deer. Other fascinating (to me) rabies statistics are available on the NC Department of Health and Human Services website. The path of rabies infection Rabies is transmitted through saliva and nervous tissue, such as brain. It usually enters the body through a bite wound but can also enter through broken skin or mucous membranes (nose, mouth, or eyes). After rabies virus enters the body, it travels through the nerves to the brain. This process can take several months. During this incubation period, the exposed animal has no symptoms of infection. Once the virus reaches the brain, it multiplies and moves to the salivary glands. At this point the animal can transmit rabies to another animal. Virus multiplication in the brain causes brain inflammation, leading to signs of rabies. Death occurs within about 7 days. Rabies virus tests in animals are performed on brain tissue. For this reason, rabies testing in animals requires euthanasia. To sum up: An animal exposed to rabies might not show signs of infection for many months and cannot be tested for rabies while it is alive. An animal that is capable of transmitting rabies will show signs of infection within a few days and will be dead within about a week. September 15, 2017 Photo by Inge Wallumrød |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed