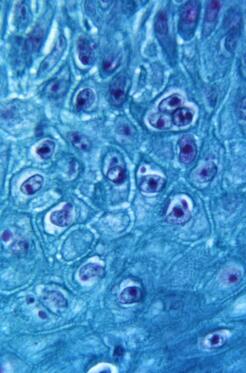

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in fecal flotation solution. Image from CDC. Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in fecal flotation solution. Image from CDC. Have you ever heard that pregnant people shouldn’t handle a cat’s litter box? This is because of the risk of toxoplasmosis. World Zoonoses Day, July 6, is a great time to talk about how this disease passes from animals to people and whether pregnant people really do get a 9-month pass on cleaning the litter box. Zoonoses are diseases that are transmitted from nonhuman animals to humans. Toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease caused by infection with the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Toxoplasmosis is one of the most common foodborne illnesses in people. The people who should be most cautious about T gondii infection are those with compromised immune systems and those who are pregnant. Toxoplasmosis in People People With Healthy Immune Systems People with healthy immune systems usually have no signs of T gondii infection and don’t know they’ve been infected. For those who develop signs, most have swollen lymph nodes or flu-like symptoms that get better on their own within a few weeks. Much less commonly, the infection can affect the eyes and cause vision loss. Whether or not the initial infection causes any signs of illness, the parasites remain in the body in a dormant state. The infected person develops immunity to T gondii. However, if the person’s immune system becomes compromised (because of chemotherapy, organ transplantation, or AIDS, for example), the T gondii organisms are reactivated and cause illness. People With Weakened Immune Systems In people with compromised immunity, toxoplasmosis affects the brain, eyes, lungs, and other organs. Either a new infection or a reactivated infection can cause seizures, confusion, and coordination problems. Fetuses Infected Before Birth A fetus won’t become infected if the mother was infected with T gondii before getting pregnant. In this case the mother already has immunity and won’t pass the infection to the unborn child (as long as she has a healthy immune system). If a mother is infected for the first time during or immediately before pregnancy, the fetus can be infected too because the mother doesn’t yet have immunity. Most people don’t know if they’ve been infected with T gondii in the past, so it’s safest for all pregnant people to take precautions to avoid infection. The consequences of infection in an unborn child can be severe. The pregnancy might end in miscarriage or stillbirth, or the fetus might develop anatomic abnormalities. More commonly, infected infants have no signs of infection when they’re born. These individuals can develop vision loss or neurologic problems years later. How People Are Infected

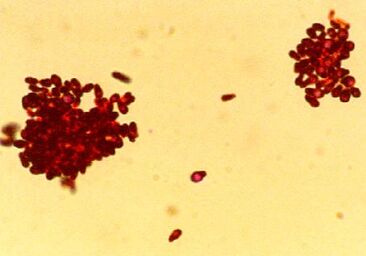

Toxoplasmosis in Cats Domestic cats and other felines are the only species that spread T gondii into the environment. Cats become infected after eating birds or rodents that have T gondii cysts in their bodies. Infected cats then shed T gondii oocysts (eggs) in the stool. The oocysts are not infective to other animals right away. After at least 1 day, the oocysts mature to a stage that can infect other animals. Infective oocysts can survive in the environment for years. Most infected cats don’t have any signs of illness. Cats with compromised immune systems can develop disease similar to that of humans with compromised immune systems. Identifying cats infected with T gondii is tricky. Cats shed oocysts in the stool for only a short time, so fecal tests aren’t reliable for diagnosing infection in cats. However, if a fecal test happens to show oocysts that look similar to T gondii, the cat’s owners should take precautions with the cat’s stool for a few weeks. A blood test showing that a cat has T gondii antibodies doesn’t tell us whether that cat is likely to start shedding oocysts that could put the family at risk. Precautions The CDC recommends these precautions to avoid toxoplasmosis:

Pregnant people should also take these precautions:

For More Information

Image source: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/toxoplasmosis/index.html Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Rafaëlla Waasdorp on Unsplash Photo by Rafaëlla Waasdorp on Unsplash All dogs are at risk for leptospirosis and should be vaccinated for it every year, according to updated recommendations from the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM). Leptospirosis is caused by infection with Leptospira bacteria. The infection spreads from animals to humans, so leptospirosis is a public health hazard. Leptospirosis is a serious disease that damages the kidneys and other organs. The leptospirosis vaccine for dogs has previously been considered a lifestyle vaccine, given to dogs with certain risk factors but not necessarily to all dogs. Information about how the disease spreads has improved over the years, so the ACVIM now says that all dogs, regardless of their lifestyle and location, should receive the vaccine. Transmission Leptospira spread mainly through urine. Many wild and domestic animal species carry the bacteria and deposit them in the environment. Rats and other rodents are the most common carriers. Leptospira grow best in water and wet soil. Dogs with access to bodies of water, especially in warm climates, are at higher risk than others. However, the infection can also spread by direct contact (for example, when dogs hunt rodents) and in other ways, so outbreaks have happened among people and dogs living in urban areas and in drier and colder climates. Cats seem to be resistant to leptospirosis, and cases in cats are extremely rare. However, cats might be able to spread the bacteria to other animals. Disease Leptospirosis affects many organ systems. These are some of the most serious problems it causes:

These are some of the signs of infection:

Diagnosis and Treatment Leptospira can be hard to detect with laboratory tests. Definite diagnosis might require multiple blood and urine tests to isolate bacterial DNA and measure antibody titers. Dogs with suspected leptospirosis also receive baseline bloodwork, urinalysis, and chest radiographs. Leptospirosis is treated with antibiotics. Additional treatments depend on the individual patient’s course of illness and the organ systems affected. Some dogs with kidney injury caused by leptospirosis need dialysis. The risk of a person contracting leptospirosis directly from an infected dog is low because dogs don’t shed many Leptospira organisms in their urine. However, people caring for a dog with leptospirosis need to take precautions like avoiding contact with the urine, wearing protective clothing, and washing hands. Vaccination The doctors at Mallard Creek recommend that all dogs receive a leptospirosis vaccine starting at 9 weeks of age. Dogs need a booster vaccine 3 to 4 weeks later and then once a year. Leptospirosis vaccines are not all the same. Leptospira have many different variations, or serovars, and vaccines target only specific serovars. However, some don’t cover the serovars currently causing disease in dogs in the United States. Your veterinarian can advise you on the best vaccination plan for your own dog. Source Sykes JE, Francey T, Schuller S, Stoddard RA, Cowgill LD, Moore GE. Updated ACVIM consensus statement on leptospirosis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2023;37(6):1966-1982. doi:10.1111/jvim.16903 Image source: https://unsplash.com/photos/a-dog-running-through-a-field-of-yellow-flowers-SEGsw2Kmd08 Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Sofia Shultz on Unsplash Photo by Sofia Shultz on Unsplash Cases of infectious respiratory disease in dogs have received media attention in the last couple of weeks. We don’t yet know what’s causing these illnesses or whether the reported cases are true outbreaks. However, there is no doubt that dogs can be exposed to a variety of infectious organisms, mostly affecting the respiratory and gastrointestinal (digestive) systems, when they’re around other dogs. Take steps to reduce your dog’s risk if your dog goes to group settings like these:

Dogs in animal shelters are at especially high risk because incoming animals are likely to be carrying infections, overcrowding is common, and stress can blunt the immune response. Infectious disease agents—viruses, bacteria, parasites, and so forth—are spread in 5 main ways: by direct contact, through the air, by mouth, by vectors (mosquitoes, ticks, and other animals), and on objects (water bowls, shoes, etc). Dogs in group settings can be exposed through any of these routes. Infectious Respiratory Disease Canine infectious respiratory disease complex, also called kennel cough, is caused by a wide range of viruses and bacteria, like canine parainfluenza virus, canine influenza virus, and Bordetella bronchiseptica. These infectious agents are carried in respiratory secretions and transmitted by direct contact with an infected dog, through the air, or on contaminated objects. Symptoms include coughing, sneezing, and runny nose. Most dogs have mild illness and recover, but some develop pneumonia. Vaccines are available for some of the agents that cause respiratory disease. Infectious Gastrointestinal Disease Canine parvovirus is highly contagious among dogs. Infection is often fatal but can be prevented with vaccination. A number of other viruses, bacteria, and protozoa that cause gastrointestinal disease are contagious among dogs. These agents are shed in feces, so transmission is generally by direct contact, by mouth, or on contaminated objects. Symptoms are related to the digestive tract: vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and so forth. Raw meat is a source of bacterial infection (E coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria, etc). Dogs that eat raw meat can shed these bacteria in their feces without showing any symptoms, and other dogs that have contact with the feces can become infected. Parasites Intestinal parasites—most often hookworms and roundworms—are common in dogs that aren’t receiving regular parasite prevention medication. These worms are contagious to other dogs (and people) through feces. External parasites like fleas and ticks are vectors that spread infectious diseases to dogs and people. Some of these diseases, like bartonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease, can be quite serious. Dogs can also catch fleas and mange mites directly from other dogs. How to Reduce Your Dog’s Risk

Image source: https://unsplash.com/photos/black-and-tan-german-shepherd-and-brown-and-black-german-shepherd-mix-dogs-on-brown-field-Z-lEcNOfWMI Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Bogdan Farca on Unsplash Photo by Bogdan Farca on Unsplash Cat scratch disease in humans is caused by infection with Bartonella henselae bacteria, which are transmitted by cat fleas. This potentially serious infection is an important reason to use flea control products for all cats all year round. Transmission Bartonella species are spread by arthropods such as fleas, lice, and sand flies. People can be infected by several species of Bartonella. In the United States, B henselae is the most common cause of disease in humans. Cat fleas shed B henselae in their feces. Cats that harbor fleas carry these bacteria on their claws, on their skin, and in their mouths. Humans are usually infected by cat scratches contaminated with flea feces. People can also be infected by being bitten or having an open wound licked by a cat carrying B henselae. Dogs can also carry B henselae, but they typically have a lower bacterial load than cats. Whether dogs can transmit the infection to humans is not known. Infection in Humans In humans, B henselae infection can cause fever and swollen lymph nodes. More rarely, it causes inflammation of the heart valves, brain, bone, joints, eyes, or other organs. People with compromised immunity, such as those with HIV infection, are more likely than others to develop serious illness from B henselae infection. Infection in Cats Cats very commonly carry B henselae. Up to 40% of shelter cats in some geographic locations have B henselae in their bloodstream. Kittens tend to carry more bacteria than adult cats. Cats carrying B henselae usually have no symptoms. Because these bacteria are well adapted to living in cats’ bodies, they very rarely make cats sick. However, some cats develop fever, vomiting, eye inflammation, or swollen lymph nodes. Bartonella infection can be difficult to diagnose in cats. No antibiotic has been shown to completely eliminate the bacteria from carrier cats, and prolonged antibiotic treatment can cause the bacteria to develop antibiotic resistance. For these reasons, testing and treatment are recommended only for cats that have signs of illness caused by Bartonella infection. Prevention Because flea control prevents B henselae transmission among cats, the American Association of Feline Practitioners recommends that all cats receive flea prevention products year round. The CDC recommends these steps to prevent B henselae infection in people:

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Infectious respiratory disease spreads easily between dogs. Public domain image from pixy.org. Infectious respiratory disease spreads easily between dogs. Public domain image from pixy.org. An outbreak of a highly infectious cough has recently been affecting dogs in the Charlotte area. The disease spreads quickly wherever dogs gather: boarding kennels, dog day cares, dog parks, and so forth. Dogs with no symptoms can spread the infection to other dogs. Most dogs have mild illness and recover at home, but some dogs develop pneumonia and need to be hospitalized. Dogs with pneumonia are at risk of dying. These are some of the signs of mild illness:

Call your veterinarian if your dog has any of the following signs:

Take your dog to an emergency clinic right away if your dog has signs of trouble breathing:

Causes Many viruses and bacteria cause canine infectious respiratory disease complex (CIRDC), sometimes called kennel cough. Dogs are often infected with more than 1 agent at the same time. These are some of the agents that cause CIRDC:

Core vaccines (standard for all dogs) give protection against some but not all of the viral agents. Noncore vaccines (optional lifestyle vaccines) are available for canine influenza virus and Bordetella. Vaccines don’t completely prevent CIRDC, but fully vaccinated dogs tend to have shorter and less severe illness. Vaccines also help limit spread of the disease. Transmission and Risk Factors The infectious agents spread through respiratory droplets and secretions. Some of the agents stay in the environment and continue to infect dogs for weeks. Dogs are infected by direct contact with an infected dog, by inhaling respiratory droplets, or by licking contaminated objects like bowls, bedding, toys, floors, walls, or people’s hands or clothes. Because CIRDC can spread silently (by dogs with no symptoms) and some of the agents persist in the environment for a long time, outbreaks can be hard to control. Any dog that has contact with other dogs or spends time in areas where dogs gather can be infected. Most dogs develop only mild illness and recover within a couple of weeks. Puppies, senior dogs, and dogs with impaired immune function are at higher risk of pneumonia. Some of the agents that cause CIRDC can also infect cats. The only CIRDC agent known to infect humans is Bordetella, but transmission to people is very rare. Canine influenza is not contagious to people. Diagnosis and Treatment The decision to pursue diagnostic tests depends on the individual dog. Dogs with mild illness need physical examination but often don’t undergo other tests if they have symptoms that suggest CIRDC, have been around other dogs (especially in an area with an outbreak of respiratory disease), and are feeling well otherwise. Additional diagnostic tests can include chest radiographs, bloodwork, tests for specific infectious agents, and tests to rule out other causes of coughing. Treatment can range from just resting at home to being hospitalized for intensive care, depending on the severity of illness. Antibiotics don’t kill viruses, but because CIRDC often involves a combination of organisms, dogs suspected to have a viral respiratory disease (like influenza) might receive an antibiotic as a precaution against bacterial infection. Prevention These are some tips to help keep your dog safe from infectious respiratory disease:

For more information

Image source: https://pixy.org/4653483/ Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by C. E. Price Photo by C. E. Price Canine parvovirus is highly contagious among dogs. Infection causes severe illness and is often fatal in dogs that do not receive intensive treatment. Risk Factors Parvovirus infection is most common in puppies that have not yet completed their initial vaccination series and in adult dogs that are not fully vaccinated against parvovirus. A recent outbreak of parvovirus in Michigan highlighted how quickly the virus can spread, especially in dogs in group housing like animal shelters. All dogs are at risk of infection, but whether a dog becomes ill depends on the dog’s level of immunity to the virus. Transmission Canine parvovirus type 2 (the version responsible for illness) infects domestic dogs and some wild animals, such as foxes, coyotes, wolves, and raccoons. The virus is shed in feces and resists drying, heat, and cold, so it stays in the environment for a long time. Dogs are infected by ingesting even a tiny amount of feces that contains parvovirus. Dogs can be infected by contact with an infected dog or with contaminated feces, surfaces, or objects. People who have handled infected dogs or contaminated objects can carry the virus on their hands or clothes and infect other dogs. Wild animals might be a source of environmental spread of parvovirus. Animals that have no symptoms can be carriers. Effects on the Body and Signs of Infection Canine parvovirus targets the lining of the small intestine, bone marrow, heart, and other organs. Destruction of the intestinal lining causes vomiting, bloody diarrhea, dehydration, loss of barrier protection against bacteria, and inability to absorb nutrients. Some infected animals develop intussusception, a potentially life-threatening condition in which a section of intestine folds into itself like a telescope. White blood cells (part of the immune system) are produced in the bone marrow, so infected animals have low white blood cell counts and impaired immune function. Because of decreased intestinal barrier protection and immune function, infected animals are at risk of septic shock caused by bacterial infection. Young puppies sometimes develop myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart muscle. These are some of the signs of parvovirus infection:

Death can occur within 3 days after symptoms begin. Diagnosis Parvovirus infection is often suspected on the basis of the patient’s symptoms, age, and vaccination history. Tests of fecal samples confirm the infection. A rapid test at a veterinary clinic is convenient but sometimes returns a false result, which can delay the diagnosis (this was the case with the outbreak in Michigan). A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at a diagnostic laboratory is accurate but takes longer. A blood test showing a low white blood cell count supports a diagnosis of parvovirus, especially in a sick puppy still awaiting a PCR test result. Dogs with parvovirus infection usually also receive other tests, such as x-ray imaging or ultrasound of the belly. Treatment For most dogs with parvovirus infection, the best chance for recovery is hospitalization for intensive care very soon after symptoms start. No antiviral drug that kills parvovirus is currently available, so treatment consists of measures to reverse dehydration, minimize vomiting and diarrhea, prevent bacterial infection, reduce pain, and restore nutrition. Intensive care for parvovirus infection can be expensive. Prognosis Most dogs that receive prompt intensive treatment in the hospital survive. Most dogs that are not treated die. For dogs whose owners can’t afford hospitalization, the success of outpatient treatment depends on the individual dog (illness severity and immune status), type of treatment, and ability of the owners to provide care at home. Prevention The parvovirus vaccine is effective and is one of the core vaccines recommended for all dogs. This vaccine is part of the initial series of puppy vaccines. Puppies need to receive the entire initial vaccine series to have the best chance of being protected. The current recommendation is for puppies to be vaccinated every 2 to 4 weeks from the ages of about 6 weeks to at least 16 weeks. The vaccine is given again 1 year later and then every 3 years throughout the dog’s life. Some dogs never mount an immune response to vaccination (this is not common). Vaccinating all dogs helps keep puppies and vulnerable adult dogs safe. Limiting a puppy’s exposure to other dogs and to places where other dogs gather reduces the risk of infection. However, this approach can hinder a puppy’s social and emotional development. In general, puppy classes and establishments that have protocols to reduce disease transmission (like requiring vaccines, proper disinfection and hygiene, and isolation of sick dogs) are relatively safe, especially when weighed against the risk of behavior problems in puppies that are not socialized. Exposure to dogs of unknown vaccination and health status, as in dog parks, is riskier. Ask your veterinarian about safe activities for your puppy, and keep your puppy away from sick dogs and other dogs’ feces. For More Information

Public domain photo by C. E. Price Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Monkeypox virus particles in skin from an infected monkey (900× magnification). Public domain image from CDC, 1968. Monkeypox virus particles in skin from an infected monkey (900× magnification). Public domain image from CDC, 1968. Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease; it spreads between animals and humans. In the United States, the chance that a person will catch monkeypox from a pet or give monkeypox to a pet is very low. Transmission between people and pets is possible, though, so the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed monkeypox guidance for pet owners. This article summarizes information from the CDC and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and is current as of August 24, 2022. See these links for updates:

How Monkeypox Spreads Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 in monkeys and since then has been found in many animal species. Rodents and other small mammals (not monkeys) are thought to be the reservoir species that maintain the virus. Human infection was first reported in 1970 in Africa, and monkeypox has occasionally appeared in other parts of the world. The United States had an outbreak in 2003 after pet prairie dogs were housed with infected animals from Ghana. The 2022 global monkeypox outbreak has involved at least 75 countries. The monkeypox virus is related to the virus that causes smallpox. The virus infects the host through the respiratory tract, mouth, eyes, or broken skin. These are some of the ways people and animals are infected:

Most transmission during the 2022 outbreak has been through close, direct contact with an infected person. Animals at Risk One pet dog has contracted monkeypox, most likely from direct contact with its owners (this was the first reported case of human-to-animal transmission). Chinchillas, prairie dogs, and some types of rabbits, mice, and rats can be infected with the monkeypox virus. Many wild mammals are also susceptible to infection. Cats, guinea pigs, hamsters, and cows can be infected with other viruses in the same genus as monkeypox, but whether they can also be infected with the monkeypox virus is not yet known. The CDC says that it’s best to assume that any mammal can be infected. There have been no reports of infection in animals that are not mammals. Signs of Monkeypox in Animals These are some of the signs that infected animals have developed:

These symptoms are nonspecific. Many conditions that are much more common than monkeypox cause the same symptoms in animals. Diagnosing monkeypox requires laboratory tests. Precautions for Pet Owners: CDC Guidance

If You Think Your Pet Has Monkeypox: CDC Guidance

Sources Monkeypox. American Veterinary Medical Association. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/one-health/veterinarians-and-public-health/monkeypox Monkeypox in animals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 17, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/veterinarian/monkeypox-in-animals.html Monkeypox: pets in the home. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 17, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/specific-settings/pets-in-homes.html Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022:S0140-6736(22)01487-8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01487-8 Image source: CDC Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Public domain image from CDC. Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Public domain image from CDC. Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in humans in the United States.[1] Dogs can be infected with the bacteria that cause Lyme disease but are much less likely than people to develop symptoms. Transmission Lyme disease is caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria, which are transmitted through tick bites. The tick responsible for infection in the eastern United States is Ixodes scapularis, the deer tick (also called the blacklegged tick). Deer ticks persist in the environment because they’re maintained in populations of deer and other wild animals. For this reason, Lyme disease is endemic—always present in the environment—in some parts of the country. Deer ticks are smaller than American dog ticks and can be hard to see on animals with fur. The immature nymph stage, which can also transmit B burgdorferi, is tiny and even harder to spot. Ticks live in woods, grassy areas, and underbrush. Ticks can’t jump or fly; they wait on the tip of a branch or grass blade until a person or animal brushes past, then they latch on. Adult deer ticks can be active when the weather is cool, so Lyme disease isn’t just a summertime risk. Ticks transmit bacteria to the host animal while they’re taking a blood meal. It takes a day or two for B burgdorferi to pass from a tick into a host, so removing ticks within 24 hours reduces the risk of Lyme disease. Humans and dogs don’t spread Lyme disease directly to each other, but dogs can bring ticks into the home. Infection in one host species also means that another host species living in the same environment is at risk. If a dog has a positive test for B burgdorferi, for example, that means the dog has been exposed to ticks carrying the bacteria, and people in the dog’s household are at risk for Lyme disease from the same ticks. Symptoms Most dogs (95%) infected with B burgdorferi don’t develop any symptoms. In dogs that become ill, symptoms start 2 to 5 months after infection and include fever, loss of appetite, and lameness that can shift from one leg to another. Some infected dogs develop kidney disease. Cats can be infected with B burgdorferi, but whether they actually get sick from the infection is unknown. Diagnosis Many dogs are routinely tested for B burgdorferi antibodies at the same time as their annual heartworm test. Antibody tests show whether a dog has been exposed to the bacteria. The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine recommends yearly antibody tests for all dogs living in or near areas where Lyme disease is endemic.[2] Dogs that test positive have further blood and urine tests to check kidney function and uncover other problems. A positive antibody test in a healthy dog also indicates a possible risk of Lyme disease for people living in the same environment. Diagnosing Lyme disease in dogs with symptoms is not always straightforward. The same symptoms are caused by many different conditions. A positive antibody test means that at some point the dog was bitten by a tick carrying B burgdorferi, not necessarily that the infection is causing the current symptoms. A diagnosis is usually based on antibody test results (possibly more than 1 type of test), symptoms consistent with Lyme disease, lack of evidence of other causes of symptoms, and response to treatment. Treatment Dogs with symptoms of Lyme disease are treated with antibiotics. Dogs that develop kidney disease need additional treatment. Prevention Tick control is the best way to prevent Lyme disease. Many tick preventives are available for dogs; some are given by mouth and others are applied to the skin. Your veterinarian can suggest products best suited to your dog. Some products are available only by prescription. The CDC website has lots of information about preventing tick bites in people and pets. See “Preventing Tick Bites” in the Lyme disease section of the CDC website: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/index.html Vaccines for Lyme disease are available for dogs. Your veterinarian can advise you on whether you should consider having your dog vaccinated. References 1. Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed June 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index.html 2. Littman MP, Gerber B, Goldstein RE, Labato MA, Lappin MR, Moore GE. ACVIM consensus update on Lyme borreliosis in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(3):887-903. doi:10.1111/jvim.15085 Ixodes scapularis image source: CDC Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Malassezia pachydermatis organisms. CDC/Janice Haney Carr. Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Malassezia pachydermatis organisms. CDC/Janice Haney Carr. Yeast skin infection (dermatitis) is common in dogs and also affects cats. Animals with allergies to pollen, grass, and other substances are especially prone to yeast dermatitis and yeast ear infections, so watch for the signs of infection if your pet gets itchy when the seasons change. Causes Yeast dermatitis is caused by Malassezia organisms on the skin. Malassezia yeasts are part of the normal collection of microorganisms that live on the skin and in the ears of animals. Yeast dermatitis occurs when something about the host animal—skin condition or immune function—causes Malassezia to overgrow or results in an abnormal immune response to Malassezia organisms. Examples of skin conditions that lead to yeast overgrowth are inflammation and increased moisture. Some animals are allergic to Malassezia and develop yeast dermatitis even when the number of organisms on the skin is relatively low. These are some of the things that increase the risk of yeast dermatitis:

Signs The most commonly affected areas are the face, neck, armpits, belly, inner thighs, feet, and ears, although yeast dermatitis can affect any part of the skin. Yeast dermatitis typically causes these signs:

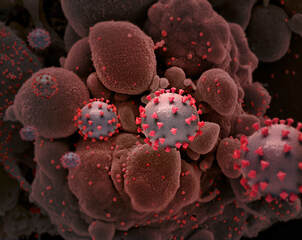

Diagnosis Samples from affected areas are taken with various methods (tape pressed to the skin, a microscope slide pressed to the skin, cotton swabs, scraping with a blade, or possibly skin biopsy) and examined under a microscope. Animals with yeast dermatitis might have very few Malassezia organisms visible with a microscope. In animals with long-term or recurring yeast dermatitis, other tests are often done to look for an underlying cause. Treatment Yeast dermatitis is treated with topical medication, oral medication, or both. Topical antifungal products include shampoos, mousses, wipes, creams, and so forth. Topical products need enough skin contact time to be effective, so shampoos usually come with instructions not to rinse the lather off for at least 10 minutes. A number of prescription oral antifungal medications are also used. The choice of treatment type—topical, oral, or both—depends on the individual animal, the part of the body affected, the response to earlier treatment, and the ability of the animal’s owner to apply topical treatments. Not everyone has a place to bathe a large shaggy dog twice a week, for instance. Treatment for yeast dermatitis typically needs to continue for weeks. For animals with recurring yeast dermatitis, the underlying cause also needs to be treated. Reference 1. Bond R, Morris DO, Guillot J, et al. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol. 2020;31(1):28-74. doi:10.1111/vde.12809 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/vde.12809 Public domain image source: CDC/Janice Haney Carr Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Creative rendition of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. Public domain. Creative rendition of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. Public domain. As COVID-19 cases increase, more pets are exposed to the virus, so it’s time to review what we know about COVID-19 and animals. The content of this article is current as of February 7, 2022. Can animals get COVID-19? A number of mammal species, including dogs and cats, can be infected with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19). Infection in animals is rare compared with infection in people. Most animals infected with the virus have had close contact with people who had COVID-19. Some species have been experimentally infected under controlled conditions; these species might or might not be able to get infected naturally. The virus has not been found in birds, reptiles, amphibians, or fish. Animals infected with SARS-CoV-2 don’t necessarily get sick. Domestic cats, large cats, dogs, ferrets, hamsters, mink, and gorillas have developed symptoms after being infected. Infection with no symptoms has been found in rabbits, bats, white-tailed deer, and many other species. Symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals are usually mild and nonspecific (lots of other things cause the same symptoms):

Can pets spread COVID-19 to people or other animals? The risk of catching COVID-19 from a pet is very low. There is no evidence that animals are a significant source of infection for people or that animals carry the virus on their fur. An exception is that SARS-CoV-2 was found to spread in both directions between mink and humans on mink farms in Denmark. Some animals can infect other animals of the same species. For example, SARS-CoV-2 spreads among white-tailed deer populations without causing symptoms. Someone in my household has COVID-19. How should I protect my pets? People with COVID-19 can spread the virus to dogs, cats, and ferrets, although serious illness is rare in animals. The CDC recommends that people with COVID-19 avoid close contact with pets, stay in a room away from pets as much as possible, and wear a mask if they need to be near pets. People carrying the infection should also wash their hands before and after handling animals, avoid sharing food with animals, and avoid kissing their pets or letting their pets lick them in the face. There is no reason to remove pets from the home unless their caregiver is unable to take care of them. Don’t put a mask on an animal or do anything else that might block its airflow. Increase ventilation or use air filters instead. Don’t use hand sanitizer, disinfecting wipes, or surface cleaners on an animal. I think my pet might have COVID-19. What should I do? If your pet has symptoms that seem similar to COVID-19, call your veterinarian. If you have COVID-19, don’t take your pet to the clinic yourself. Your veterinarian will advise you on whether your pet should be seen at the clinic. Can I have my pet tested for COVID-19? Don’t use a home test on an animal. Routine animal testing for COVID-19 is not currently recommended because infection is rare in animals, the symptoms are more likely to be caused by something else, and animals aren’t a significant source of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Decisions about animal testing are made by a veterinarian in consultation with public health officials. A veterinarian will need to rule out more common causes of the symptoms before considering SARS-CoV-2 testing. Testing might be done for animals that meet criteria like having exposure to an infected person and having symptoms compatible with SARS-CoV-2 infection (with no other cause found). Can my pet be vaccinated for COVID-19? Vaccines for dogs and cats are not available. According to the World Organisation for Animal Health, vaccines are being developed for some animal species that are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. An experimental COVID-19 vaccine has been given to zoo animals at risk of getting sick from the infection. Mink will likely also be a priority species for vaccine development because of their potential to spread the infection to humans. Please see these sources for updates and more information:

Public domain image credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. Source: NIH Image Gallery |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed