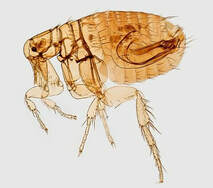

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Microchips are a type of permanent identification that helps families reunite with lost pets. Pets should also have visible forms of identification like collar tags, but microchips can’t be pulled off by accident and are an important backup. Microchips are also required in some situations, like transporting animals. Microchips connect owners to lost pets only if the owner’s contact information is registered in a microchip database. The United States does not have a central microchip registry. Microchip manufacturers and pet recovery services maintain their own databases. It’s essential to keep your contact information up to date in your pet’s microchip database. If you’re not sure where your pet’s microchip is registered, enter the microchip number in the American Animal Hospital Association microchip lookup tool: http://www.petmicrochiplookup.org/ If you don’t know the microchip number, your veterinarian’s office can scan your pet if the number is not already entered in your pet’s medical record. What Are Microchips? Microchips are radiofrequency identification transponders about the size and shape of a grain of rice. Microchips are implanted under the skin. In dogs and cats, they are implanted between the shoulder blades. You can’t usually feel a microchip under your pet’s skin, but you can see it on an x-ray image. A microchip is not a GPS device and can’t be used to track your pet. How Are Microchips Implanted? A microchip is injected under the skin through a needle, similar to the way a vaccine is injected (although the needle is a bit larger). Animals do not need anesthesia during microchip insertion. Your veterinarian can implant a microchip during an office visit. How Does Scanning Work? Shelters and veterinary clinics routinely scan stray dogs and cats for microchips. If the animal has a microchip and the owner’s information in the database is accurate, the staff can contact the owner. A microchip scanner emits a low-power radiofrequency signal that activates the microchip. When a microchip scanner passes over a microchip, the chip transmits a number that the scanner displays on a screen. The number is unique to that microchip, so once you’ve registered it, it’s also unique to your pet. Microchip manufacturers around the world make microchips that use different radiofrequencies. Not all scanners detect all microchip frequencies. Universal scanners read multiple frequencies. Microchips that meet the International Standards Organization (ISO) global standard transmit a specific radiofrequency that can be read by an ISO-standard scanner. Some countries require ISO-compliant microchips for imported animals. Are Microchips Safe? The benefits of microchipping are generally far greater than the potential risks. Adverse reactions to microchips are rare. Animals could bleed a little or have mild, short-lived discomfort at the injection site. Infection and swelling at the injection site are possible but not common. Microchips can theoretically cause inflammation that leads to cancer, but almost all reports of cancer near a microchip implantation site have been in laboratory rodents. Only a few cases in cats and dogs have been reported, and in most it was not clear if the cancer was linked to the microchip. Are Microchips Reliable? It’s possible for an animal to have a microchip that isn’t found on a scan. A microchip might use a different radiofrequency than the scanner can detect (if the scanner isn’t universal). Microchips occasionally migrate under the skin, usually to the side of the shoulder or front leg. People scanning for microchips typically scan a wide area of the body for this reason. And a microchip might not work at all (or stop working). Ask your veterinarian to check your pet’s microchip at the next clinic visit. For more information, see Microchipping of Animals FAQ on the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) website. The AVMA Microchipping of Animals backgrounder page was also a source for this article. Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Fleas don’t just cause itching. They also carry infectious diseases that can be contagious to people. Controlling fleas on your pets protects your whole family’s health. Tapeworms Tapeworms are parasites that live in the intestines. They shed small body segments called proglottids that pass out of the host animal’s body in the feces. Tapeworm segments in the stool look like whitish rice grains. Fleas transmit a type of tapeworm that commonly infects dogs and cats. Dogs and cats become infected by swallowing a flea. Tapeworms rarely cause significant disease in dogs and cats. The dog and cat tapeworm that is carried by fleas, Dipylidium caninum, can also infect humans (usually children) who swallow a flea.[1] Bartonellosis (Cat Scratch Disease) Bartonella species are bacteria that cause a variety of diseases in humans and other animals. Cat scratch disease and endocarditis (heart valve infection) are just 2 of the serious illnesses caused by Bartonella infection.[2] Fleas are the most common insect vector for Bartonella henselae, the species that causes cat scratch disease.[3] Fleas can also carry other Bartonella species. Infected cats and dogs might or might not have any symptoms of infection. Bartonellosis is a human health risk. Treating your cat with a cat-safe flea preventive reduces the risk of cat scratch disease for people in contact with your cat. Rickettsial Diseases Rickettsiae are a group of bacteria responsible for diseases such as typhus and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Rickettsiae are spread by arthropods, including fleas and ticks. The types of fleas that infest dogs and cats transmit Rickettsia typhi (which causes murine typhus) and Rickettsia felis. Both of these bacteria can also cause disease in people.[1,4] Yersiniosis (Plague) Plague, including bubonic plague and the Black Death, is caused by infection with the bacterium Yersinia pestis. The Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) transmits the bacterium usually to rodents but sometimes to cats, dogs, other animals, and humans. Rat fleas in the western United States and other parts of the world still harbor Yersinia.[3] Mycoplasma Infection Cats infected with certain types of Mycoplasma bacteria develop anemia (low red blood cell count). Fleas are thought to be a source of infection for cats.[5] Noninfectious Diseases Fleas cause skin disease in animals that scratch or chew themselves to relieve the itch. Just a few fleas can set off intense itching in an animal with a flea allergy. Because fleas feed on blood, animals with lots of fleas can develop anemia from blood loss. This anemia can be life threatening. References 1. Fleas. Companion Animal Parasite Council website. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/fleas/. Updated September 19, 2017. Accessed May 7, 2019. 2. Bartonella infection (cat scratch disease, trench fever, and Carrión’s disease). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/bartonella/index.html. Updated December 14, 2015. Accessed May 7, 2019. 3. Shaw SE. Flea-transmitted infections of cats and dogs. World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2008. Veterinary Information Network website. https://www.vin.com/doc/?id=3866578. Accessed May 7, 2019. 4. Little SE. Feline fleas and flea-borne disease (proceedings). DVM360 website. http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/feline-fleas-and-flea-borne-disease-proceedings. Published April 1, 2010. Accessed May 7, 2019. 5. Lappin MR. Update on flea and tick associated diseases of cats. Vet Parasitol. 2018;254:26-29. Photo of Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) by James Gathany, CDC |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed