Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Heartworms are parasites transmitted by mosquitoes. The worms grow to be several inches long and live in the heart, lungs, and blood vessels of the lungs. Cats are infected less often than dogs but can die of heartworm disease. There are currently no good options for removing heartworms in cats. Giving cats heartworm preventive medication all year round is the best way to protect them from heartworm disease. Infection in Cats Cats can be infected with heartworms wherever dogs are infected with heartworms—and heartworms have been diagnosed in dogs in all 50 states.[1] Studies have shown that 12% to 16% of cats have been exposed to heartworms.[2] In a 2017 study, 15% of cats with heartworm infection were indoor cats.[3] Animals become infected with heartworms through mosquito bites. Mosquitoes take in heartworm microfilariae (baby heartworms) when they bite an infected dog, coyote, or other canid. When the mosquito bites another animal, heartworm larvae are deposited in the other animal’s body. Over the next few months, the larvae travel to the blood vessels and eventually to the heart. Dogs are heartworms’ natural hosts. Cats are atypical hosts, which means that heartworms aren’t as well adapted to living in cats. In dogs, heartworm larvae grow up to be adults that can make baby heartworms. Heartworms in cats are less likely to produce offspring. Heartworms that reach adulthood in cats are usually smaller than in dogs and don’t live as long (heartworms can live for 2-4 years in cats and 5-7 years in dogs).[2] Cats typically have only a few heartworms, whereas dogs can have many. However, because cats and their hearts are so small, even 1 or 2 worms are a significant burden for them. Symptoms In cats, heartworm disease is mainly a lung disease. Most of the symptoms are caused by an inflammatory reaction to worms in the lungs and the blood vessels of the lungs. Although some cats never show any signs, others have a severe inflammatory response that leads to a condition called heartworm-associated respiratory disease. The symptoms of this disease can be mistaken for asthma. Symptoms of heartworm infection in cats can include the following:

Diagnosis Diagnosis of heartworm infection is not always straightforward in cats. Antigen tests are used routinely in dogs, and a cat with a positive antigen test is definitely infected. But antigen tests detect only adult female heartworms. These tests are more likely to miss infections in cats than in dogs because cats are sometimes infected with only immature worms (no adults) or with only 1 or 2 worms (which might not be female). Antibody tests show whether cats have been exposed to heartworms but not whether they are still infected. Heartworm diagnosis in cats usually involves a combination of antigen testing, antibody testing, and possibly ultrasound to look for worms in the heart and the blood vessels of the lungs. Chest radiographs can show changes compatible with heartworm disease. Cats also typically receive general bloodwork including a complete blood count and chemistry profile. Treatment In cats, the goals of treatment are to reduce the inflammatory response and provide support until symptoms improve or the infection clears on its own. The level of treatment depends on the individual cat’s condition and symptoms. Cats with severe disease may need intensive care. The drug used to eliminate heartworms in dogs is not recommended for cats because it is more toxic to cats. No medications so far have been shown to be effective and safe for removing heartworms in cats. Surgical removal of heartworms may be attempted in some cats but has risks. Studies of other treatment options are ongoing.[1] Prevention Safe and effective monthly heartworm preventives are available for cats and kittens. Some products are flavored chews; others are drops applied to the skin. All heartworm preventives in the United States require a prescription from a veterinarian. No over-the-counter products are effective at preventing heartworms in dogs or cats. For More Information Heartworm in cats (American Heartworm Society): https://www.heartwormsociety.org/heartworms-in-cats Heartworm in cats (Cornell Feline Health Center): https://www.vet.cornell.edu/departments-centers-and-institutes/cornell-feline-health-center/health-information/feline-health-topics/heartworm-cats References 1. American Heartworm Society. Prevention, diagnosis, and management of heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection in cats. Published 2020. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://d3ft8sckhnqim2.cloudfront.net/images/pdf/2020_AHS_Feline_Guidelines.pdf?1580934824 2. Heartworm: cat. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Updated July 1, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/heartworm/ 3. Levy JK, Burling AN, Crandall MM, Tucker SJ, Wood EG, Foster JD. Seroprevalence of heartworm infection, risk factors for seropositivity, and frequency of prescribing heartworm preventives for cats in the United States and Canada. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;250(8):873-880. Photo by Rana Sawalha

0 Comments

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  New information about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to emerge as the pandemic progresses. The information in this article is current on the date of posting (April 1, 2020). For the most recent updates, see the resources linked at the end of the article. Can pets get sick with COVID-19? This question is still being investigated. A vast number of pets have lived with people with COVID-19 without getting sick, so the risk of human-to-animal transmission is probably extremely low. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has not had any reports of animals in the United States getting sick with COVID-19. There have been rare reports of pets in other countries having positive tests for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. (A positive test for a virus doesn’t necessarily mean the virus will cause illness in that animal. It also doesn’t show whether the animal can pass the virus to another animal.) These animals each lived with a person with confirmed COVID-19 and were almost certainly exposed by the infected person. Two dogs in Hong Kong had positive tests for SARS-CoV-2 but had no symptoms (they didn’t actually get sick with COVID-19). One cat in Belgium reportedly had a positive test and symptoms, but because of missing or questionable evidence about this cat, the World Organisation for Animal Health has not confirmed this as an infection. Can pets spread COVID-19 to people? Multiple infectious disease experts and international health organizations say there is currently no evidence that dogs and cats can spread the COVID-19 virus to people. There is no need to avoid, neglect, or surrender pets out of fear of COVID-19. (This has reportedly been happening in some places.) Pets and people live in close contact and can share other diseases, so health organizations recommend washing your hands after handling animals and practicing good hygiene in general. Can pet hair or accessories (leashes, food bowls, etc) transmit the COVID-19 virus to people? According to the most recent data and guidance, transmission through pet accessories is theoretically possible but hasn’t been shown to actually happen. SARS-CoV-2 mainly spreads from person to person. Touching an object that has virus particles on it and then touching your face could possibly transmit the virus, but this route is not considered a major source of infection. If the virus can be transmitted through pet hair or accessories at all, transmission is probably more likely with smooth, solid objects like food bowls than with porous or fibrous objects like hair. Coronaviruses can stay on surfaces for hours or days, according to the World Health Organization. The virus particles might or might not be able to infect a person during that whole time, depending on the environmental conditions. Although it seems unlikely that the virus would be transmitted by a leash, food bowl, or pet hair, it’s always a good idea to clean pet accessories regularly and wash your hands after handling an animal. If someone in my household has COVID-19, how should I protect my pets? The CDC recommends that people who have COVID-19 stay separated from pets. CDC guidance states that people with COVID-19 should “avoid direct contact with pets, including petting, snuggling, being kissed or licked, sleeping in the same location, and sharing food.” This guidance does not apply to service animals, who can stay with their handlers. If possible, someone who does not have COVID-19 should take over the pet care. People with COVID-19 who have to continue caring for their pets (including service animals) should wash their hands before and after handling their pets. The American Veterinary Medical Association adds that people with COVID-19 should wear a face mask around their animals and shouldn’t share food, dishes, or bedding with them. No one is recommending that pets wear face masks, in case you were wondering. Face masks could actually harm animals by hindering their breathing. How should I prepare for pet care in case I get sick with COVID-19? Plan ahead, just as you prepare for natural disasters like hurricanes. Identify someone who can take care of your pets if you’re unable to. Make sure you have a couple of weeks’ worth of pet food and medications. Check your supply of monthly heartworm and flea preventives and contact your veterinarian if you need a refill. If your pet has medical needs, be ready to provide a list of instructions for another caregiver. Consider preparing a letter for your veterinarian authorizing your backup caregiver to approve treatments. If my pet needs to see a veterinarian, what should I do? Contact your veterinarian to find out if your pet should go the clinic. Depending on local guidance, the clinic might be postponing non-urgent procedures to help reduce community spread of COVID-19. Some clinics might be able to treat established patients through telemedicine (virtual visits). Under North Carolina’s current stay-at-home order, veterinary clinics are considered essential businesses. Your pets can still get the care they need. If your pet needs to be seen at the clinic, you will probably be asked to stay outside the building while your pet is taken inside to help keep you and the clinic staff safe. If I am (or might be) sick with COVID-19 and my pet needs to see a veterinarian, what should I do? Call the clinic. Your clinic might not have sufficient personal protective equipment for staff to use when handling animals from a household with COVID-19. Your veterinarian might be able to treat your pet via telemedicine or refer you to a clinic with available protective equipment. If your veterinarian confirms that your pet should come to the clinic, have someone else (ideally not living in your household) transport your pet to the clinic. For more information and updates:

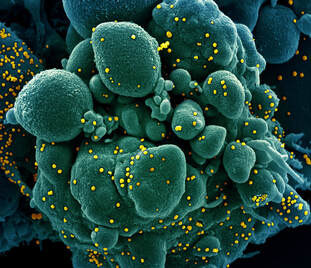

Image: colorized scanning electron micrograph of cell infected with SARS-CoV. Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH; https://www.flickr.com/photos/nihgov/49680300342/. |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed