Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in fecal flotation solution. Image from CDC. Toxoplasma gondii oocysts in fecal flotation solution. Image from CDC. Have you ever heard that pregnant people shouldn’t handle a cat’s litter box? This is because of the risk of toxoplasmosis. World Zoonoses Day, July 6, is a great time to talk about how this disease passes from animals to people and whether pregnant people really do get a 9-month pass on cleaning the litter box. Zoonoses are diseases that are transmitted from nonhuman animals to humans. Toxoplasmosis is a zoonotic disease caused by infection with the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Toxoplasmosis is one of the most common foodborne illnesses in people. The people who should be most cautious about T gondii infection are those with compromised immune systems and those who are pregnant. Toxoplasmosis in People People With Healthy Immune Systems People with healthy immune systems usually have no signs of T gondii infection and don’t know they’ve been infected. For those who develop signs, most have swollen lymph nodes or flu-like symptoms that get better on their own within a few weeks. Much less commonly, the infection can affect the eyes and cause vision loss. Whether or not the initial infection causes any signs of illness, the parasites remain in the body in a dormant state. The infected person develops immunity to T gondii. However, if the person’s immune system becomes compromised (because of chemotherapy, organ transplantation, or AIDS, for example), the T gondii organisms are reactivated and cause illness. People With Weakened Immune Systems In people with compromised immunity, toxoplasmosis affects the brain, eyes, lungs, and other organs. Either a new infection or a reactivated infection can cause seizures, confusion, and coordination problems. Fetuses Infected Before Birth A fetus won’t become infected if the mother was infected with T gondii before getting pregnant. In this case the mother already has immunity and won’t pass the infection to the unborn child (as long as she has a healthy immune system). If a mother is infected for the first time during or immediately before pregnancy, the fetus can be infected too because the mother doesn’t yet have immunity. Most people don’t know if they’ve been infected with T gondii in the past, so it’s safest for all pregnant people to take precautions to avoid infection. The consequences of infection in an unborn child can be severe. The pregnancy might end in miscarriage or stillbirth, or the fetus might develop anatomic abnormalities. More commonly, infected infants have no signs of infection when they’re born. These individuals can develop vision loss or neurologic problems years later. How People Are Infected

Toxoplasmosis in Cats Domestic cats and other felines are the only species that spread T gondii into the environment. Cats become infected after eating birds or rodents that have T gondii cysts in their bodies. Infected cats then shed T gondii oocysts (eggs) in the stool. The oocysts are not infective to other animals right away. After at least 1 day, the oocysts mature to a stage that can infect other animals. Infective oocysts can survive in the environment for years. Most infected cats don’t have any signs of illness. Cats with compromised immune systems can develop disease similar to that of humans with compromised immune systems. Identifying cats infected with T gondii is tricky. Cats shed oocysts in the stool for only a short time, so fecal tests aren’t reliable for diagnosing infection in cats. However, if a fecal test happens to show oocysts that look similar to T gondii, the cat’s owners should take precautions with the cat’s stool for a few weeks. A blood test showing that a cat has T gondii antibodies doesn’t tell us whether that cat is likely to start shedding oocysts that could put the family at risk. Precautions The CDC recommends these precautions to avoid toxoplasmosis:

Pregnant people should also take these precautions:

For More Information

Image source: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/toxoplasmosis/index.html Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by kevin turcios on Unsplash Photo by kevin turcios on Unsplash The differences between heartworm prevention products can be confusing. Some products protect pets from other parasites in addition to heartworms. Your veterinarian can recommend products for your own pet according to risk factors like your pet’s lifestyle, environment, and geographic location. Heartworm preventives should be given all year round. If your pet’s heartworm preventive doesn’t also cover for fleas and intestinal parasites like roundworms and hookworms, your pet should receive a second product or have regular parasite tests (your veterinarian can advise you about this). Heartworm preventives labeled for dogs and cats are available in the United States only by prescription. Some products that target fleas, ticks, and intestinal parasites are prescription products; others can be sold without a prescription. If you find a flea/tick product or a dewormer for dogs or cats that can be bought without a prescription, it won’t protect your pet against heartworm infection (unless it’s being sold illegally or possibly from outside the United States). These are the parasites most often covered by parasite preventives for dogs and cats:

Heartworm Preventives New products come on the market regularly. Products within the same brand line that have different ingredients (for different parasite coverage) tend to have nearly identical names, so check labels carefully. The following is a summary of currently available heartworm preventives for dogs and cats, listed by route of administration and active ingredient. This list is from the American Heartworm Society website, which shows the product names and their parasite coverage in an easy-to-read chart. For an updated list of heartworm preventives for dogs, cats, and ferrets, please see the American Heartworm Society website: https://www.heartwormsociety.org/preventives Products for Dogs Tablets or chews given by mouth once a month:

Injectable product given every 6 or 12 months:

Topical products applied to the skin once a month:

Products for Cats Tablets or chews given by mouth once a month:

Topical products applied to the skin once a month (except Bravecto Plus):

Image source: https://unsplash.com/photos/rls2bfqYh8E Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Lucas Ludwig Photo by Lucas Ludwig Pets need stool tests to screen for parasites or help find the cause of diarrhea and other digestive system problems. Collecting a stool sample at home is the least stressful option for the pet. The alternative is for someone at the veterinary clinic to use a loop to remove a little bit of stool from the rectum. This option yields a much smaller sample and can be unpleasant for the animal. A fecal test for parasites involves mixing the stool sample in a flotation solution and either spinning it in a centrifuge or leaving it to sit in a vial for a certain amount of time. The material at the top of the solution is then removed to a microscope slide to look for parasite eggs that have floated to the surface. Sometimes a tiny bit of stool is smeared directly onto a microscope slide for examination. Fecal analysis can also include chemical tests. For all of these tests, the stool needs to be fresh and squishy enough to mix or smear. The age and condition of a stool sample affect the results. Parasite eggs can dry out or hatch in old stool. Hard, dry feces is very difficult or impossible to prepare for testing. Stool that has been sitting outdoors for a while can contain fly eggs or larvae (maggots). Liquid diarrhea that’s soaked into paper or cloth can’t be mixed in solution to test for parasites. Here’s how to collect a stool sample to get the most accurate results:

Photo by Lucas Ludwig on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Photo by Madalyn Cox Photo by Madalyn Cox Ear mites are common in cats and dogs. They cause significant ear itching and inflammation and are contagious between animals. In cats, ear mites are the most common cause of external ear disease. Ear mites affect dogs too, but external ear disease in dogs is more often caused by allergies. Ear mites (Otodectes cyanotis) are tiny parasites similar to the mites that cause mange. They live in the ears and are sometimes also found on skin elsewhere on the body. Ear mites feed on natural skin debris like ear wax. They stay on the skin surface and don’t burrow into the skin, unlike some other mites. Ear mites spread easily through close contact between animals. People are not thought to be at risk from cat and dog ear mites. It’s possible but very rare for ear mites to affect humans. Signs The signs of ear mites are similar to the signs of ear infections caused by bacteria and yeast. Animals can have ear mites without showing any symptoms, but most animals have these signs:

Diagnosis Bacterial and yeast ear infections cause signs similar to ear mites, so don’t assume that a cat or dog with itchy ears has ear mites. An animal with suspected ear mites should see a veterinarian to look for ear mites and rule out other ear problems that would need a different type of treatment. Some animals have ear mites and a bacterial or yeast ear infection at the same time. Ear mites are easiest to see with magnification, either in a sample of ear debris under a microscope or through an otoscope inserted into the ear (if the animal’s ears aren’t too painful). Sometimes the mites are visible in ear debris without magnification; they look like pinpoint white specks that move. Treatment In the past, treating ear mites meant instilling an oily liquid into the animal’s ears daily for about 3 weeks. This type of product is still available over the counter without a prescription, but don’t use an over-the-counter remedy without first taking your pet to see a veterinarian. Newer prescription products kill ear mites more quickly, some in only 1 or 2 doses, and some don’t require putting drops directly into the ears. Because ear mites are contagious, it’s best to treat all dogs and cats in the household. For More Information See these links for more information and photos of ear mites:

Photo by Madalyn Cox on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Coccidia are tiny parasites that live in the intestines. Coccidia infection is common in dogs and cats, most often affecting puppies and kittens. Infection can cause severe disease and even death, especially in young animals, although some infected animals have no symptoms at all. Coccidia are protozoa, which are single-celled organisms. They are not worms, and deworming medications do not remove coccidia. Different species of coccidia infect different animals. Coccidia that infect dogs and cats are in the genus Isospora. Other types of coccidia infect other mammals (including humans), birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians. Unlike some parasites, coccidia that infect dogs and cats are not contagious to humans. Coccidia are host specific: they cause disease only in their own host species, not in animals of other species. Dogs with coccidia spread the disease to other dogs but not to cats or humans. Cats with coccidia spread the disease only to other cats. Transmission Coccidia that infect dogs and cats are transmitted through feces. Dogs and cats are usually infected by swallowing contaminated soil or other contaminated substances in the environment. They can also be infected by eating a small animal (like a rodent or insect) that serves as a transport host or vector for Isospora organisms. Coccidia in the feces are not infective right away. The life stage that passes out of the body in the stool is immature (nonsporulated). After a few hours in the environment, this stage matures to the sporulated stage, which can infect other animals. Sporulated coccidia can survive in the environment for a year.[1] Symptoms After sporulated coccidia are swallowed, they release other stages that invade cells of the intestines. Damage to the intestinal cells is responsible for the symptoms. Puppies, kittens, and adult animals with compromised immune systems are at most risk for serious illness. These are some of the symptoms:

Diagnosis Coccidia are diagnosed by examining a sample of feces under a microscope. Sometimes infected animals have false-negative test results (no coccidia seen even though the animal is infected), so animals with symptoms might need repeated fecal tests to diagnose the cause of illness. Coccidia can also be found in the feces of animals with no symptoms. Treatment Coccidia infection is treated with medication from a veterinarian. Complete treatment may take a few days or a few weeks, depending on the severity of infection. Sanitation of the environment reduces the chance of reinfection during treatment, especially for animals in group housing. Medications that remove hookworms, roundworms, and other common dog and cat parasites do not affect coccidia. Heartworm, flea, and tick preventives also do not remove or prevent coccidia. Prevention Because coccidia in stool aren’t infective for a few hours, removing feces from the environment regularly (at least once a day) helps prevent infection. Keeping cats indoors reduces or eliminates their exposure risk. Preventing dogs and cats from hunting rodents and other animals also reduces their chance of infection from transport hosts. All dogs and cats—and especially puppies and kittens—should have periodic fecal tests by a veterinarian. Reference 1. Coccidia. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Updated October 1, 2016. Accessed February 19, 2021. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/coccidia/ Photo by David Clarke Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Whipworms are intestinal parasites that are relatively common in dogs and can cause serious illness. Some (not all) monthly heartworm preventives prevent whipworm infection. Canine whipworms are small worms about 2 to 3 inches long that live in the cecum, a pouchlike structure attached to the large intestine. The whipworm that infects dogs, Trichuris vulpis, does not infect humans. (Another species of whipworm can infect people.) Whipworms are very rare in cats in North America. According to the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC), almost 50,000 dogs in the United States tested positive for whipworms in 2019. About 2500 of these dogs were in North Carolina, putting North Carolina in the CAPC high-risk category for whipworms.[1] Transmission Dogs are infected with whipworms when they swallow whipworm eggs in the environment—for example, by licking dirt from their feet.[2] The eggs hatch in the dog’s intestines and grow to adult worms in the cecum. About 2.5 to 3 months after the dog is infected, the adult worms begin producing eggs that pass out of the body in the feces. Whipworm eggs in the environment take about 2 to 3 weeks (or longer) to develop into a stage that can infect dogs. This means that dogs are infected by swallowing contaminated substances, not by eating fresh dog poop. Whipworm eggs in the environment are resistant to temperature changes and sunlight and are able to infect dogs for years.[3] Symptoms Symptoms of whipworm infection depend partly on the number of worms present and can include the following:

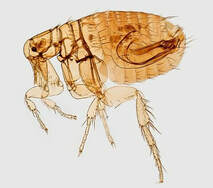

Diagnosis Whipworm infection can be a little tricky to diagnose. Typical fecal analysis at a veterinary clinic involves looking for worm eggs in a stool sample under a microscope. However, because whipworms don’t produce eggs for the first few months after infection and they don’t produce eggs all of the time, stool analysis with a microscope can miss the infection. Sending a fecal sample to a diagnostic laboratory for a whipworm antigen test can increase the chance of finding the infection. Treatment and Prevention Antiparasitic drugs to treat whipworm infection are typically given in at least 2 doses spaced a few weeks apart. Monthly heartworm preventives that contain milbemycin (given by mouth) or moxidectin (applied to the skin) will treat and prevent whipworm infection.[3] Other heartworm preventives available at the time of writing (May 2020) are not effective against whipworms. It’s not possible to completely eliminate whipworm eggs that are already in the environment. The CAPC recommends reducing dogs’ risk by removing dog feces from the environment and regularly testing dogs for whipworms. References 1. Parasite prevalence map: 2019, whipworm, dog, United States. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://capcvet.org/maps/#2019/all/whipworm/dog/united-states/ 2. Brooks W. Whipworm infection in dogs and cats. Veterinary Partner. Published May 8, 2004. Updated July 18, 2018. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/doc/?id=4952061&pid=19239 3. Trichuris vulpis. Companion Animal Parasite Council. Updated October 1, 2016. Accessed May 20, 2020. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/trichuris-vulpis/ Image: photomicrograph of Trichuris vulpis egg, 400× magnification. Credit: CDC/Dr Mae Melvin. Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Fleas don’t just cause itching. They also carry infectious diseases that can be contagious to people. Controlling fleas on your pets protects your whole family’s health. Tapeworms Tapeworms are parasites that live in the intestines. They shed small body segments called proglottids that pass out of the host animal’s body in the feces. Tapeworm segments in the stool look like whitish rice grains. Fleas transmit a type of tapeworm that commonly infects dogs and cats. Dogs and cats become infected by swallowing a flea. Tapeworms rarely cause significant disease in dogs and cats. The dog and cat tapeworm that is carried by fleas, Dipylidium caninum, can also infect humans (usually children) who swallow a flea.[1] Bartonellosis (Cat Scratch Disease) Bartonella species are bacteria that cause a variety of diseases in humans and other animals. Cat scratch disease and endocarditis (heart valve infection) are just 2 of the serious illnesses caused by Bartonella infection.[2] Fleas are the most common insect vector for Bartonella henselae, the species that causes cat scratch disease.[3] Fleas can also carry other Bartonella species. Infected cats and dogs might or might not have any symptoms of infection. Bartonellosis is a human health risk. Treating your cat with a cat-safe flea preventive reduces the risk of cat scratch disease for people in contact with your cat. Rickettsial Diseases Rickettsiae are a group of bacteria responsible for diseases such as typhus and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Rickettsiae are spread by arthropods, including fleas and ticks. The types of fleas that infest dogs and cats transmit Rickettsia typhi (which causes murine typhus) and Rickettsia felis. Both of these bacteria can also cause disease in people.[1,4] Yersiniosis (Plague) Plague, including bubonic plague and the Black Death, is caused by infection with the bacterium Yersinia pestis. The Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) transmits the bacterium usually to rodents but sometimes to cats, dogs, other animals, and humans. Rat fleas in the western United States and other parts of the world still harbor Yersinia.[3] Mycoplasma Infection Cats infected with certain types of Mycoplasma bacteria develop anemia (low red blood cell count). Fleas are thought to be a source of infection for cats.[5] Noninfectious Diseases Fleas cause skin disease in animals that scratch or chew themselves to relieve the itch. Just a few fleas can set off intense itching in an animal with a flea allergy. Because fleas feed on blood, animals with lots of fleas can develop anemia from blood loss. This anemia can be life threatening. References 1. Fleas. Companion Animal Parasite Council website. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/fleas/. Updated September 19, 2017. Accessed May 7, 2019. 2. Bartonella infection (cat scratch disease, trench fever, and Carrión’s disease). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/bartonella/index.html. Updated December 14, 2015. Accessed May 7, 2019. 3. Shaw SE. Flea-transmitted infections of cats and dogs. World Small Animal Veterinary Association World Congress Proceedings, 2008. Veterinary Information Network website. https://www.vin.com/doc/?id=3866578. Accessed May 7, 2019. 4. Little SE. Feline fleas and flea-borne disease (proceedings). DVM360 website. http://veterinarycalendar.dvm360.com/feline-fleas-and-flea-borne-disease-proceedings. Published April 1, 2010. Accessed May 7, 2019. 5. Lappin MR. Update on flea and tick associated diseases of cats. Vet Parasitol. 2018;254:26-29. Photo of Oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) by James Gathany, CDC Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Adult heartworms grow up to a foot long, block blood flow around the heart, and cause inflammation within blood vessels. The damage continues as long as the heartworms remain in the body. Heartworm treatment protocols for dogs are designed to remove the worms while reducing the risk of treatment complications. No safe heartworm treatment exists for cats and ferrets. Your veterinarian can recommend appropriate heartworm preventives for your dog, cat, or ferret. Initial Tests Heartworm infection is diagnosed with a blood test. Your veterinarian might confirm the diagnosis with another test before proceeding with treatment. Other tests, like x-ray imaging, echocardiography (heart ultrasound), and other blood tests, are used to assess the extent of damage. The results can affect the treatment plan, so your veterinarian might recommend these tests even if your dog isn’t showing any symptoms of infection. Dogs with blood clotting problems or signs of heart disease need a full diagnostic workup before treatment starts. Exercise Restriction Any activity that increases the heart rate and blood pressure can worsen the problems caused by heartworms. Dogs with heartworms need to stay as quiet as possible to limit the damage. Once treatment begins, pieces of dead worms can break off and lodge in small blood vessels, potentially causing serious problems and even death. Strict exercise restriction is the best way to reduce the risk. The American Heartworm Society (AHS) recommends restricting activity from the time heartworms are diagnosed until 6 to 8 weeks after the last dose of heartworm treatment. Dogs should ideally stay indoors in a small area where they can’t run or jump. Some dogs need to be confined to a crate. They should go outdoors on a leash only long enough to pee and poop. Ask your veterinarian about the level of confinement your dog needs. Before Killing the Heartworms Before dogs begin receiving adulticide (medication that kills adult heartworms), they may need treatment for heartworm-related problems. They should receive a certain type of heartworm preventive to remove larvae, or immature worms, from the bloodstream. They also benefit from a monthlong course of doxycycline, an antibiotic, to eliminate a bacterium that lives inside heartworm cells. This bacterium is partly responsible for the inflammation that occurs when heartworms die. The AHS recommends that dogs start adulticide treatment 2 months after receiving a heartworm diagnosis (30 days after the last dose of doxycycline). Dogs should have limited activity during these 2 months. Adulticide Treatment The only adulticide currently approved for use in the United States is melarsomine. This drug is given by injection in a veterinary hospital. Your dog may need to stay in the hospital for observation after a melarsomine injection. The number and timing of injections may vary depending on the situation. The current AHS recommendation is to give a series of 3 injections: 1 injection followed by a 30-day wait, then 2 injections given 24 hours apart. Your veterinarian will suggest a protocol that’s appropriate for your own dog. Complete exercise restriction is crucial during adulticide treatment and for several weeks after the last dose. Your veterinarian may also prescribe medications to reduce adverse effects of treatment. Retesting Your dog can be retested for heartworms several months after the last melarsomine injection. The goal of treatment is to remove all stages of heartworms. “Slow-Kill” Methods Protocols to manage heartworm infection without using melarsomine are sometimes called “slow-kill” treatments. These protocols consist of giving doxycycline for a month and beginning a specific type of heartworm preventive to remove larvae. Heartworms take from several months to a year or more to die with these protocols. The disadvantage of slow-kill treatment is that it allows adult heartworms to remain in the body for much longer than with adulticide treatment. The worms continue to damage the heart and blood vessels during this time. For this reason, the AHS does not recommend this method as standard treatment. Dogs receiving slow-kill treatment should also have exercise restriction for as long as adult heartworms remain in the body. The advantage of slow-kill treatment is that it costs much less than melarsomine. Slow-kill methods have been proposed for dogs that would otherwise go untreated or be euthanized, like those in shelters or in areas where melarsomine is not available. Slow-kill treatment also offers an option for dogs at high risk of complications from adulticide treatment. For More Information See these resources from the American Heartworm Society: Battling Boredom: Tips for Surviving Cage Rest (PDF) Heartworm Positive Dogs: What Happens if My Dog Tests Positive for Heartworms? Heartworm Treatment Guidelines for the Pet Owner (PDF) Photo by Ryan McGuire Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Roundworms are some of the most common internal parasites in dogs and cats. They can also infect humans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 13.9% of people in the United States have antibodies to roundworms, meaning they have been exposed to the parasite at some point in their lives. How dogs and cats are infected Almost all puppies are born with roundworms. The type of roundworm that most often infects dogs, Toxocara canis, transfers from a mother dog to unborn pups through the placenta. T canis can also pass to puppies through the mother’s milk. Infected animals excrete roundworm eggs in their stool, so dogs can be infected by eating feces or swallowing roundworm eggs in the environment. Dogs can also become infected by eating a small animal (like a rodent) that is carrying roundworms. The most common roundworm in cats is Toxocara cati. Cats and kittens are usually infected by swallowing roundworm eggs in the environment or by eating an infected animal. T cati does not pass to unborn kittens through the mother’s placenta. Ingested T canis and T cati eggs hatch into larvae in the intestines. The larvae migrate through body tissues to the lungs, are coughed up and swallowed, grow into adult worms in the intestines, and begin producing eggs that pass into the environment through the feces. Roundworm larvae can remain dormant in body tissues of adult animals instead of maturing in the intestines. These arrested-development larvae can’t be detected by fecal tests for worm eggs because they don’t produce eggs. Dormant larvae in a pregnant dog can become active and move through the placenta to the pups. In other words, a female dog with a negative test for roundworms can pass roundworms to her puppies anyway. Signs of infection Infected animals often have no symptoms at all. Dogs and cats (especially puppies and kittens) with lots of roundworms may develop a potbelly, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, or dull coat. Heavily infected animals sometimes vomit worms, which look a bit like spaghetti noodles, or pass worms in the stool. Treatment and prevention in pets Young puppies and kittens should receive multiple doses of deworming medication. The Companion Animal Parasite Council recommends deworming puppies and kittens every 2 weeks starting at age 2 weeks for pups and 3 weeks for kittens, continuing until they are about 2 months old, and then beginning monthly parasite preventives. Many heartworm preventives also prevent roundworm infection. To reduce the chance your pets will be infected, remove feces from the environment and try to keep them from eating rodents or other wild animals. Have your veterinarian regularly test your pets for parasites, and give them parasite preventives all year round. Infection in humans People can be infected by T canis or T cati if they ingest contaminated dirt or feces. Toxocara eggs can survive in the soil for years. Children and people who own dogs or cats have an increased risk of infection, says the CDC. Many people with Toxocara infection don’t develop serious disease and have no symptoms. But T canis and T cati larvae can migrate through the bodies of humans, as they do in dogs and cats. Larvae that migrate to internal organs (such as the liver) damage these tissues, a disease process called visceral larval migrans or visceral toxocariasis. Symptoms depend on the organs affected. Sometimes larvae migrate to the eye, causing a disease known as ocular larval migrans or ocular toxocariasis. People with this condition may develop retinal inflammation and vision loss. Prevention in humans The CDC recommends these steps to prevent toxocariasis:

For more information Ascarid (Companion Animal Parasite Council) Cat Owners: Roundworms and Dog Owners: Roundworms (Pets and Parasites) Toxocariasis FAQs (CDC) Photo by Berkay Gumustekin Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Are you tempted to skip your pets' heartworm and flea medicines during the winter? Dogs and cats actually need parasite prevention all year round. Year-round parasite control for pets helps keep the whole family safe from parasite-transmitted disease. Warm spells during the winter are common in North Carolina, so we can’t count on cold temperatures to suppress insects that carry disease. Mosquitoes, fleas, and ticks can also live through the winter in areas that are protected from the cold. Heartworms Heartworms are transmitted by mosquitoes. Mosquitoes become active when the temperature rises above about 50°F (which happens routinely in North Carolina during the winter). But occasional warm winter days aren’t the only reason pets need year-round heartworm prevention. Heartworm preventives work by killing tiny heartworm larvae that are already in an animal’s bloodstream. These larvae came from mosquitoes that bit the animal in the past month or more. Skipping a month of heartworm prevention could mean that your dog isn’t protected from heartworm larvae that he was exposed to when it was warmer. The American Heartworm Society recommends giving heartworm preventives all year round. Intestinal parasites (worms) Some heartworm preventives also control intestinal parasites like hookworms and roundworms. These parasites can infect humans too. Giving parasite prevention to your pets throughout the year is a sensible safety measure. Fleas Fleas don’t just causing itching. They also transmit diseases like cat scratch disease, tapeworms, and plague. Fleas lay eggs that drop off the infested animal into the environment. This means that flea eggs are present everywhere the animal has been, including inside a home. After the eggs hatch, the larvae and pupae (intermediate stages) can stay dormant for weeks to months before becoming adult fleas. Because fleas can go through their life cycle indoors, they don’t need to wait for warm weather to develop into adult fleas. Flea infestations are easier to prevent than to treat, so the best chance of avoiding a flea problem is to give your pets year-round flea prevention. Ticks Ticks carry many diseases that affect both pets and people. Some tick species, including the type that transmits Lyme disease, are active during the winter when the temperature is above freezing. Ticks tend to live in leaf litter, crevices of buildings, and underbrush. When they’re ready to take a blood meal, they move to grassy areas or shrubbery near paths and latch onto a passing animal or person. Ticks can be hard to see through fur, so you might not realize that your dog has picked up a tick. Because of the risk of serious disease, the safest approach is to limit tick exposure: control ticks around your home and give your pets tick preventives recommended by your veterinarian. Photo by Justin Veenema |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed