Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Hal Gatewood on Unsplash Photo by Hal Gatewood on Unsplash Over-the-counter (nonprescription) pain medications can cause serious problems for dogs and cats. Because these medications don’t need a prescription and are used for children as well as adults, some pet owners mistakenly believe that they’re safe for animals too. But dogs and cats don’t process these drugs the same way as humans. If your pet has signs of pain, call your veterinarian instead of giving your pet something from your medicine cabinet. Prescription pain medications developed specifically for dogs and cats are safer and more effective for them than over-the-counter human medications. In any case, animals that have a level of pain high enough to be obvious to a human need to see a veterinarian. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (Aspirin, Ibuprofen, Naproxen) The most common human nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) available without a prescription are aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen. Some brand names are Advil, Aleve, Ascriptin, Bayer, Bufferin, Ecotrin, Midol, and Motrin. In animals, NSAIDs can cause these problems:

NSAIDs reduce inflammation by blocking the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are responsible for prostaglandin production. Prostaglandins are hormone-like substances with many functions; they’re involved in the inflammatory response and also protect the stomach lining and maintain blood flow to the kidneys. Because NSAIDs decrease prostaglandin levels, these medications decrease inflammation and pain. However, the lower prostaglandin levels can also cause serious adverse effects like stomach ulcers and kidney damage. Some newer NSAIDs target specific COX enzymes and prostaglandins that are less likely to affect the stomach and kidneys. Several NSAIDs have been approved for use in dogs, and a few are available for cats. Examples are carprofen, grapiprant, deracoxib, and robenacoxib. These species-specific drugs are available only by prescription from a veterinarian and are less likely than human NSAIDs to cause adverse effects in dogs and cats. Animals receiving prescription NSAIDs need regular examinations and bloodwork to monitor kidney and liver function. Acetaminophen Brands containing acetaminophen include Tylenol, Panadol, Excedrin, and Midol. Some pain relievers labeled “complete” or “dual action” contain acetaminophen plus aspirin or ibuprofen. Acetaminophen is also called paracetamol. Acetaminophen is highly toxic and often fatal to cats. Acetaminophen is also potentially toxic to dogs, but it can be used in dogs with caution and veterinary oversight. In humans and dogs, acetaminophen is broken down mainly in the liver through a process called glucuronidation. A toxic dose of acetaminophen in a human or a dog damages liver cells and causes liver failure. Cats don’t have the enzymes needed for glucuronidation, so their bodies break down acetaminophen through a different process called sulfation. The sulfation process in cats creates products that react to hemoglobin, the substance within red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body. In cats, acetaminophen exposure causes anemia and life-threatening oxygen deficiency. Cats that swallow acetaminophen are less likely than dogs to develop liver failure because they usually die of oxygen deficiency before the liver has a chance to fail. An antidote to acetaminophen (N-acetylcysteine) is available, so dogs and even cats with acetaminophen poisoning can recover if they are treated immediately at an emergency veterinary clinic. For More Information Get the Facts About Pain Relievers for Pets (US Food and Drug Administration): https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-health-literacy/get-facts-about-pain-relievers-pets Image source: https://unsplash.com/photos/round-white-pills-iPl3q-gEGzY Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Sofia Shultz on Unsplash Photo by Sofia Shultz on Unsplash Cases of infectious respiratory disease in dogs have received media attention in the last couple of weeks. We don’t yet know what’s causing these illnesses or whether the reported cases are true outbreaks. However, there is no doubt that dogs can be exposed to a variety of infectious organisms, mostly affecting the respiratory and gastrointestinal (digestive) systems, when they’re around other dogs. Take steps to reduce your dog’s risk if your dog goes to group settings like these:

Dogs in animal shelters are at especially high risk because incoming animals are likely to be carrying infections, overcrowding is common, and stress can blunt the immune response. Infectious disease agents—viruses, bacteria, parasites, and so forth—are spread in 5 main ways: by direct contact, through the air, by mouth, by vectors (mosquitoes, ticks, and other animals), and on objects (water bowls, shoes, etc). Dogs in group settings can be exposed through any of these routes. Infectious Respiratory Disease Canine infectious respiratory disease complex, also called kennel cough, is caused by a wide range of viruses and bacteria, like canine parainfluenza virus, canine influenza virus, and Bordetella bronchiseptica. These infectious agents are carried in respiratory secretions and transmitted by direct contact with an infected dog, through the air, or on contaminated objects. Symptoms include coughing, sneezing, and runny nose. Most dogs have mild illness and recover, but some develop pneumonia. Vaccines are available for some of the agents that cause respiratory disease. Infectious Gastrointestinal Disease Canine parvovirus is highly contagious among dogs. Infection is often fatal but can be prevented with vaccination. A number of other viruses, bacteria, and protozoa that cause gastrointestinal disease are contagious among dogs. These agents are shed in feces, so transmission is generally by direct contact, by mouth, or on contaminated objects. Symptoms are related to the digestive tract: vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and so forth. Raw meat is a source of bacterial infection (E coli, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria, etc). Dogs that eat raw meat can shed these bacteria in their feces without showing any symptoms, and other dogs that have contact with the feces can become infected. Parasites Intestinal parasites—most often hookworms and roundworms—are common in dogs that aren’t receiving regular parasite prevention medication. These worms are contagious to other dogs (and people) through feces. External parasites like fleas and ticks are vectors that spread infectious diseases to dogs and people. Some of these diseases, like bartonellosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and Lyme disease, can be quite serious. Dogs can also catch fleas and mange mites directly from other dogs. How to Reduce Your Dog’s Risk

Image source: https://unsplash.com/photos/black-and-tan-german-shepherd-and-brown-and-black-german-shepherd-mix-dogs-on-brown-field-Z-lEcNOfWMI Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Elisa Kennemer on Unsplash Photo by Elisa Kennemer on Unsplash Warm weather brings some extra risks for pets. Some animals need protection from sunlight, and all animals need protection from hot temperatures. Sun-Related Skin Conditions Ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight causes skin damage in animals just like it does in humans. Fur and melanin (dark pigment) protect the skin from UV rays, so animals with short white hair or no hair are at higher risk than those with thick dark fur. Most animals with sun-related skin disease spend a lot of time outdoors, but even indoor cats can develop skin disease caused by UV rays coming through windows. Sun-related skin damage typically affects areas of the body that don’t have thick fur and are exposed to the sun. Any part of the body with thin or light-colored hair can be involved, but these are the most common areas:

Solar dermatitis, also called actinic dermatitis, is skin disease caused by exposure to UV radiation. It can be mistaken for allergic skin disease because the lesions are similar and it is often seasonal. Affected skin is red, painful to the touch, and scaly or flaky. Bumps and oozy lesions might develop. Over time, the skin becomes thickened and scarred. Because solar dermatitis usually causes a secondary skin infection, the lesions might improve with antibiotics, at least at first. UV radiation causes mutations within skin cells, so solar dermatitis can transform into skin cancer (squamous cell carcinoma or hemangiosarcoma, for example). These cancers are malignant: they can spread throughout the body. Solar dermatitis and skin cancer are diagnosed with skin biopsy. Heat Stroke Heat stroke is a life-threatening risk to animals during warm weather. Unlike solar dermatitis and skin cancer, it doesn’t require direct exposure to UV rays. The outdoor temperature doesn’t even have to be very hot for an animal to develop heat stroke. The temperature inside a parked car quickly rises higher than the outside temperature, so animals inside parked cars are at risk even in moderately warm weather. Brachycephalic (short-nosed) animals like pugs and bulldogs are at especially high risk. Signs of heat stroke include panting, dark red or purple gums, vomiting, collapse, and seizures. Heat stroke requires immediate first aid (cooling with water, not ice) and emergency veterinary care. For more information, see the blog post on heat stroke. How to Protect Your Pet The best way to protect animals is to minimize their exposure to UV rays and heat:

Sources

Image source: Elisa Kennemer on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Research-grade Cannabis sativa plant. Photo credit: NIDA/NIH (US government work). Research-grade Cannabis sativa plant. Photo credit: NIDA/NIH (US government work). Animal exposures to marijuana have increased dramatically in recent years. As more states legalize medical or recreational marijuana for human use, more pets are likely to have access to cannabis products. To keep things clear, here are a few terms used to describe cannabis products:

Sources of Exposure Edible products account for most THC exposures in pets. Edible products made with butter or oil infused with medical-grade marijuana have a high concentration of THC. Edible products can also contain other ingredients, like chocolate and xylitol, that are dangerous for animals. Cannabis plants are also a risk for animals. The THC content of cultivated C sativa has increased over time and varies among plants, so it’s hard to know just how much THC an animal that eats part of a cannabis plant or inhales the smoke has received. Vaping devices containing CBD, THC, or synthetic cannabinoids have caused toxicosis in animals. Animals have also been poisoned by eating marijuana in discarded cannabis products and—this one is gross—human feces. CBD products have been reported to cause poisoning in animals. It’s possible that the toxic effects were caused by contamination with THC or another substance, not the CBD itself, but the effects of CBD on animals are still being investigated. Another concern with CBD is that it might interact with prescribed medications, possibly affecting liver function. Signs Marijuana toxicosis makes animals sick but is rarely fatal. However, 2 dogs have died after eating baked goods containing medical-grade marijuana butter. Signs of poisoning start within a few minutes to several hours after exposure, depending on the type of exposure. These are some of the signs of marijuana toxicosis in animals:

Exposure to THC or synthetic cannabinoids can also cause changes in heart rate, inability to regulate body temperature, aggression, seizures, and coma. Diagnosis Over-the-counter human urine tests for marijuana don’t work well in dogs and tend to return either false-positive or false-negative results. The diagnosis of marijuana toxicosis is usually based on clinical signs, although many diseases and other toxins can cause the same signs. Knowing that an animal could have been exposed to marijuana certainly makes the diagnosis easier, but owners aren’t always willing to tell a veterinarian that their pet had access to a cannabis product. Treatment Whether an animal with marijuana poisoning needs to be hospitalized depends on the severity of the signs. Treatment is mostly supportive care, with medication used as needed to treat specific problems (like heart rate abnormalities). Inducing vomiting can be unsafe, so an animal that has eaten a cannabis product might need to be sedated so the stomach can be emptied through a tube. The prognosis is usually good for animals with marijuana poisoning. The risk is higher for animals exposed to medical-grade marijuana products or synthetic cannabinoids. Sources

Image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nida-nih/28147221034/in/photostream/ Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Adult southern copperhead. Photo credit: CDC/James Gathany. Adult southern copperhead. Photo credit: CDC/James Gathany. Spring is the start of snake season in North Carolina. The vast majority of snakes in our state are harmless. Only a few venomous snake species (copperheads, cottonmouths, rattlesnakes, and coral snakes) live in North Carolina. In the Charlotte-Mecklenburg area, the copperhead is by far the most common venomous snake. Learn to recognize copperheads. Copperheads have a distinctive hourglass pattern that from the side looks like a row of Hershey’s kisses. It’s easier to identify a copperhead by its markings than by the shape of its head or pupils. Head shape isn’t a reliable way to tell if a snake is venomous; some nonvenomous snakes can flatten their heads to mimic a pit viper’s triangular head. As for pupil shape (round vs vertical slits)—seriously, just don’t get close enough to a wild snake to check. You can see photos of North Carolina snakes on the Herps of NC website: https://herpsofnc.org/snakes/. You’ll notice that copperheads and also a lot of nonvenomous snakes are brown with splotches. This color combination is common because it’s great camouflage, but unfortunately it means that nonvenomous snakes are often mistaken for copperheads. Don’t worry too much about identifying a snake that’s bitten your dog. Treatment is based more on symptoms than on snake species, and it’s more important to get your dog to an emergency clinic without delay. If you want to identify a snake you’ve seen outdoors, take a photo so you can look it up online, but don’t approach or disturb the snake. Dogs get bitten because they’re curious, not because snakes are aggressive attack animals. Snakes hide in small spaces where they’re relatively safe from predators and can find food (mostly small rodents like mice). Woodpiles, tarps, underbrush, tall grass, leaf litter, rock crevices, and yard debris are all possible snake habitats. Snakes bite for defense. A dog that steps on a snake or sticks its nose into a snake’s hiding place can be bitten. Because of their color camouflage, copperheads are hard to spot. You and your dog might not even know a copperhead is there unless it bites one of you. Avoid snake areas. If you see a snake, leave it alone and walk away. Here are some ways to reduce your dog’s chance of a snake encounter:

If your dog is bitten, seek emergency veterinary care right away. Copperhead venom isn’t as toxic as cottonmouth or rattlesnake venom, but a copperhead bite can still be quite serious for a dog. Copperhead bites are very painful and cause swelling and tissue damage. The venom can also interfere with blood clotting. Dogs with snakebite are usually hospitalized for pain management, intravenous fluids, wound care, supportive care, and observation. Copperhead bites aren’t often treated with antivenin, but dogs with severe symptoms might need it. If your dog is bitten, stay calm and take your dog to an emergency clinic. Don’t use ice, a tourniquet, or anything to remove venom from the wound; all of these can make the tissue damage worse. Leave the snake alone. If you try to catch or kill it, you could be bitten too. CDC image source: https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=10841 Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Antonio Jose Cespedes on Pixabay Photo by Antonio Jose Cespedes on Pixabay Laundry and dish detergents contain chemicals that are unsafe for animals. Detergent pods pose a bigger risk than bottled liquid detergents or detergent powders. Toxic Ingredients Detergents contain anionic and nonionic surfactants, which lift dirt and oil off of surfaces and fabrics. These types of surfactants cause mild irritation to the skin and eyes. If swallowed, they can cause vomiting. Fabric softeners, disinfectants, and sanitizing solutions sometimes contain cationic surfactants, which are more corrosive than anionic and nonionic surfactants. Cats are especially sensitive to cationic surfactants. Direct contact can injure the skin, and cats that lick these products from their paws or fur can also have damage to the mouth and digestive tract. Some detergents are alkaline (they have a high pH, the opposite of acids). Concentrated alkaline products damage the stomach if swallowed. Detergents might also contain ethanol and other potentially toxic ingredients. Detergent Pods Animals (mainly dogs) that bite detergent pods are at higher risk than animals that lick liquid detergents or detergent powders. Even when the ingredients are similar, the consequences of exposure are more serious with detergent packaged in pods. Detergent in pods is concentrated and under pressure. When a tooth punctures a pod, the detergent sprays the inside of the mouth, from where it is swallowed, inhaled into the lungs, or both. Animals that lick spilled liquid detergent aren’t likely to consume very much of it because it doesn’t taste good. In comparison, dogs that bite detergent pods get a larger dose of product at a higher concentration. The most severe effects of detergent exposure are lung inflammation and pneumonia, which happen when detergent—or vomit that contains detergent—is inhaled into the lungs. Pneumonia can be fatal, so it’s possible for dogs that chew detergent pods to die. Signs of Detergent Toxicosis

If Your Pet Is Exposed

Sources

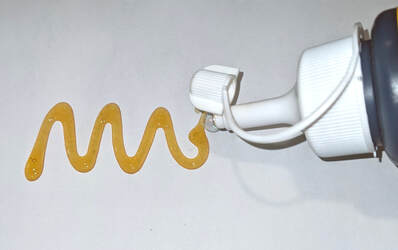

Image source: Antonio Jose Cespedes on Pixabay Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Polyurethane glues that expand when they’re exposed to moisture pose a serious risk to dogs that chew the container and swallow even a little bit of the product. Some (not all) Gorilla Glue products are expanding adhesives. Some wood glues, craft glues, general household glues, and construction adhesives also expand when wet. Dogs rarely swallow expanding adhesives, but the potential consequences can be severe. Anything that swells up when it’s wet is hazardous if swallowed. With expanding adhesives, the risk is even greater: these products expand to a size much larger than the amount swallowed and then harden to form a solid mass that can block material from entering or leaving the stomach. Expanding adhesives contain diisocyanates, which are chemicals used to make polyurethane products. Diisocyanates are hygroscopic, meaning they absorb moisture from the air. Glues that contain diisocyanates are used to seal cracks and fill gaps. In the moist, acidic environment of the stomach, products containing diisocyanates expand up to 8 times their original volume. Expansion starts within minutes after the product is swallowed. The hardened mass of glue becomes a foreign object in the stomach. A volume of glue as small as half an ounce can form a mass large enough to cause a blockage.[1] Glue that has cured before being swallowed—has already finished expanding and has formed a solid mass—is much less of a chemical risk, although of course it could still cause an obstruction if a dog managed to swallow a big enough chunk. Diisocyanates also irritate the skin and respiratory system, but these problems are much less common in animals than in people who are exposed to high levels at work. Signs and Diagnosis A mass of glue in the stomach causes the same signs as any other foreign object: vomiting, loss of appetite, painful abdomen, and loss of energy. Glue ingestion is diagnosed, or at least strongly suspected, when a dog is seen swallowing glue, the dog’s owner finds a chewed glue container, or the dog has glue residue on the fur. The mass formed by a diisocyanate glue is visible on radiographs (x-ray images) but can look very similar to food in the stomach. Other imaging tests or a series of radiographs taken over time might be needed to definitely diagnose a foreign object in the stomach. Expanding adhesives don’t stick to the inside of the stomach, luckily. In a study of dogs treated for Gorilla Glue ingestion, the glue irritated the stomach lining and caused ulcers in some dogs but didn’t cause serious damage to the stomach in any dog. The dogs had bloodwork abnormalities similar to those caused by vomiting in general or any type of stomach obstruction. Whether the presence of diisocyanates in the stomach caused any other problems wasn’t clear.[1] Treatment A foreign object that’s causing a stomach obstruction needs to be surgically removed. If a mass of glue seems small enough to pass on its own and the dog doesn’t have any worrisome signs like belly pain, the veterinarian and dog’s owner might decide to watch and wait. What to Do if Your Pet Is Exposed

Reference 1. Friday S, Murphy C, Lopez D, Mayhew P, Holt D. Gorilla Glue ingestion in dogs: 22 cases (2005-2019). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2021;57(3):121-127. doi:10.5326/JAAHA-MS-7126 Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Yew is highly toxic to animals and people. Yew is highly toxic to animals and people. Some decorative winter holiday plants pose risks to pets. Other plants that aren’t actually toxic can still cause upset stomach if an animal swallows them. If you think your pet might have swallowed or been exposed to a toxic plant, contact your veterinarian, an animal emergency clinic, or a 24-hour animal poison control hotline (a fee may apply):

Amaryllis (Amaryllis species) Ingestion of amaryllis leaves, stems, or bulbs can cause drooling, vomiting, diarrhea, belly pain, lethargy, and a drop in blood pressure. Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera species) Christmas cactus isn’t toxic. However, an animal that swallows part of one might vomit or have diarrhea. Christmas rose, hellebore (Helleborus niger) Hellebores contain cardiac glycosides, compounds that affect heart function. Ingestion of any part of the plant can cause drooling, belly pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and lethargy. Christmas trees The Christmas trees most commonly grown in North Carolina (firs, pines, cedars, and cypress) aren’t toxic, although like other non-food plants they could cause vomiting or intestinal blockage if an animal swallowed enough of one. The risks to pets are from trees falling, ornaments breaking, exposure to electrical cords, and possibly exposure to preservatives (which are not very toxic but can cause mild vomiting, according to ASPCA Animal Poison Control). Norfolk Island pines and rosemary plants are often sold as potted miniature holiday trees. These two plants aren’t toxic to cats and dogs. However, a miniature tree made of mixed greenery would be a serious danger if it contained yew. Cyclamen (Cyclamen species) Ingestion of cyclamen, a flowering houseplant, can cause drooling, vomiting, and diarrhea. Swallowing a large amount of cyclamen tubers can lead to heart rhythm abnormalities, seizures, and death. Delphinium, larkspur (Delphinium species) Blue delphinium flowers are included in some Hanukkah floral arrangements. Toxic compounds in delphinium block a neurotransmitter that’s required for muscle function. Ingestion can cause digestive system problems (vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation), belly pain, drooling, weakness, abnormal heart rhythm, tremors, seizures, and paralysis. The most severe effects—heart or lung failure and death—are most likely to happen in grazing animals that ingest large amounts of the plant. Holly, winterberry, Christmas holly, English holly (Ilex aquifolium) Ingestion of English holly and similar plants in the genus Ilex can cause vomiting and diarrhea. The pointed leaves can injure the inside of the mouth, leading to drooling and other signs of mouth discomfort. Lily (Lilium species, Hemerocallis species) Lilies of various types are common in floral arrangements, including arrangements for winter holidays. Some lilies are so toxic to cats that they shouldn’t be brought at all into a house with cats. The most dangerous lilies are Lilium species (Easter lily, Japanese lily, Asiatic hybrid lilies, stargazer lily, Casablanca lily, and tiger lily) and Hemerocallis species (daylily). Ingestion of a tiny amount of plant material—even licking pollen from a paw—can cause kidney injury in cats. Calla lilies, peace lilies, lily of the valley, and Peruvian lilies are not Lilium and Hemerocallis species; these plants don’t damage the kidneys but can cause stomach upset and other problems. Mistletoe (Phoradendron species, Viscum album) Mistletoe ingestion can cause vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain in animals. Swallowing large amounts can cause low heart rate, a drop in blood pressure, uncoordinated gait, and seizures. American mistletoe (Phoradendron species) is less toxic than European mistletoe (Viscum album). Paperwhite (Narcissus papyraceus) Paperwhites and other Narcissus species (like jonquils and daffodils) cause severe vomiting and diarrhea if ingested. Swallowing a large amount can lead to breathing and heart rhythm abnormalities. The most toxic part of the plant is the bulb. Poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima) Poinsettias are not as toxic as some have been led to believe, according to ASPCA Animal Poison Control. The thick, milky sap is an irritant that can cause drooling and vomiting if ingested. The sap can also irritate the skin and eyes on contact. Yew (Taxus species) Plants in the genus Taxus are highly toxic to all animals, including dogs, cats, horses, and people. Yew branches and berries are sometimes used to make holiday wreaths and other decorations. Be very careful displaying and disposing of items that might contain yew; be sure pets and wildlife can’t access them. Yew ingestion causes vomiting, muscle tremors, difficulty breathing, heart failure, seizures, and death. Sources

Public domain photo of yew (Taxus baccata) by MM on Wikimedia Commons Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Amy Starr Photo by Amy Starr Dogs and cats can’t have pumpkin spice lattes or Halloween candy, but not all foods that we associate with fall are off the menu for our pets. If you’d like to give treats to your pets, keep these precautions in mind:

Homemade and store-bought pet treats Many recipes for homemade dog and cat treats are available. Making your own pet treats can be a fun family project and a great outlet for creativity. Kids might be surprised that their dog is so enthusiastic about a baked dog biscuit that tastes like cardboard to them. It’s a good reminder that pets don’t need the sugar, salt, and flavorings that humans prefer. Pet food manufacturers know a marketing opportunity when they see one, so you can also find themed seasonal treats for sale. Store-bought pet treats are fine as long as they don’t contain a problem ingredient (always check labels). Pumpkin Plain cooked or canned pumpkin is safe, and dogs and cats tend to like it. If you use canned pumpkin, be sure to get plain pumpkin and not pumpkin pie filling. The sugar and spices in pie filling can cause problems. Likewise, don’t give a pet a piece of pumpkin pie—and especially not sugar-free pie, which might contain xylitol. White potatoes and sweet potatoes Most dogs love potatoes of any type. Skip the butter, salt, and toppings, though: no loaded baked potatoes or sweet potato casserole for pets. Other vegetables and fruits Many vegetables and fruits (not grapes!) are safe, tasty, low-calorie treats for pets. As always, stick with plain, unseasoned items for animals. Avoid casseroles, which might contain problem ingredients like onion and fat. To avoid a choking risk, cut raw vegetables and fruits into small pieces and remove seeds, cores, and thick peels. These are some good options:

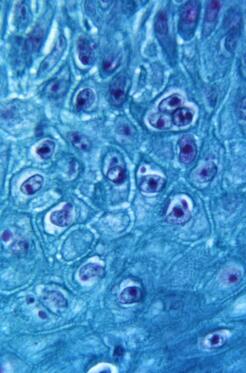

Turkey A bite of cooked lean poultry meat is safe for dogs and cats. Avoid giving pets skin, fat, bones, pan drippings, raw meat, or meat seasoned with onion. Popcorn Is popcorn a fall food? I think it depends on which Thanksgiving cartoons you watch. As with other foods, don’t add butter, salt, or seasonings to popcorn pieces you toss to your pets. Air-popped popcorn doesn’t have added fat, so it’s safer than oil-popped or microwaved popcorn for animals like schnauzers that have an increased risk for pancreatitis. Photo by Amy Starr on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Monkeypox virus particles in skin from an infected monkey (900× magnification). Public domain image from CDC, 1968. Monkeypox virus particles in skin from an infected monkey (900× magnification). Public domain image from CDC, 1968. Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease; it spreads between animals and humans. In the United States, the chance that a person will catch monkeypox from a pet or give monkeypox to a pet is very low. Transmission between people and pets is possible, though, so the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed monkeypox guidance for pet owners. This article summarizes information from the CDC and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and is current as of August 24, 2022. See these links for updates:

How Monkeypox Spreads Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 in monkeys and since then has been found in many animal species. Rodents and other small mammals (not monkeys) are thought to be the reservoir species that maintain the virus. Human infection was first reported in 1970 in Africa, and monkeypox has occasionally appeared in other parts of the world. The United States had an outbreak in 2003 after pet prairie dogs were housed with infected animals from Ghana. The 2022 global monkeypox outbreak has involved at least 75 countries. The monkeypox virus is related to the virus that causes smallpox. The virus infects the host through the respiratory tract, mouth, eyes, or broken skin. These are some of the ways people and animals are infected:

Most transmission during the 2022 outbreak has been through close, direct contact with an infected person. Animals at Risk One pet dog has contracted monkeypox, most likely from direct contact with its owners (this was the first reported case of human-to-animal transmission). Chinchillas, prairie dogs, and some types of rabbits, mice, and rats can be infected with the monkeypox virus. Many wild mammals are also susceptible to infection. Cats, guinea pigs, hamsters, and cows can be infected with other viruses in the same genus as monkeypox, but whether they can also be infected with the monkeypox virus is not yet known. The CDC says that it’s best to assume that any mammal can be infected. There have been no reports of infection in animals that are not mammals. Signs of Monkeypox in Animals These are some of the signs that infected animals have developed:

These symptoms are nonspecific. Many conditions that are much more common than monkeypox cause the same symptoms in animals. Diagnosing monkeypox requires laboratory tests. Precautions for Pet Owners: CDC Guidance

If You Think Your Pet Has Monkeypox: CDC Guidance

Sources Monkeypox. American Veterinary Medical Association. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/one-health/veterinarians-and-public-health/monkeypox Monkeypox in animals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 17, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/veterinarian/monkeypox-in-animals.html Monkeypox: pets in the home. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated August 17, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/specific-settings/pets-in-homes.html Seang S, Burrel S, Todesco E, et al. Evidence of human-to-dog transmission of monkeypox virus. Lancet. 2022:S0140-6736(22)01487-8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01487-8 Image source: CDC |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed