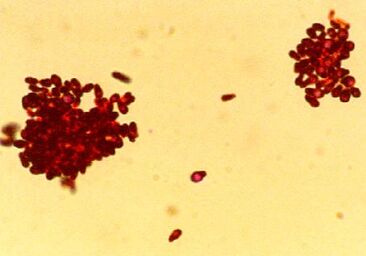

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photo by Alvan Nee Photo by Alvan Nee Prepare for pet injuries and emergencies by collecting first aid supplies in advance. You can purchase a pet first aid kit or make your own. Some of the items in a family first aid kit can also be used for animals. Emergency clinic contact information Keep a list of phone numbers of emergency clinics in your area and at travel destinations. Include animal poison control phone numbers in your list. Emergency clinics can be very busy, so if possible have contact information for multiple clinics in case the nearest one has a long wait. Call the clinic before you arrive if your pet’s condition allows time for this. Vaccination records and medical history The most important vaccination record for an emergency clinic to have is the rabies vaccination. A list of current medications and medical conditions will also be helpful, especially if someone who is less familiar with your pet’s medical history (like a pet sitter) might be taking your pet for treatment. Your primary care veterinary clinic might be closed when your pet needs emergency treatment, so have written medical records available for the emergency service. Muzzle Animals in pain can bite even if they are friendly at other times. A muzzle will help you transport your dog safely. The best type of muzzle for a dog is a basket muzzle that allows the dog to pant. You can find inexpensive basket muzzles at pet stores and online. If you plan in advance, you can reduce your dog’s anxiety about using a muzzle during an emergency by training your dog to like wearing a muzzle. See the Muzzle Up Project for tips on muzzle training. (Short version: muzzles are treat baskets!) Don’t try to put a muzzle on a dog if you would be bitten in the attempt. Emergency muzzle alternatives include a leash, rope, necktie, or bandage material wrapped around the mouth. Items that hold the mouth completely closed should never cover the nostrils, should be used only for a very short time (just to get the animal into the car), and should not be used for animals that are vomiting. Another option is to cover the animal’s head with a towel or blanket, but take extra care—animals can bite through cloth, especially if they’re frightened or in pain. Leash or pet carrier A slip leash might be easier than a clip leash to put on a scared dog. For cats, consider keeping a hard plastic carrier with a top that can be removed. If you’ve picked up your cat with a towel, you can bundle both the cat and the towel into the bottom half of the carrier and then reattach the top half. Gauze sponges and nonstick pads Plain gauze squares are used to absorb blood and drainage but are uncomfortable if they stick to a wound. If you’re bandaging a wound, use a nonstick pad as the inner layer (touching the wound) and add layers of plain gauze over the nonstick pad as needed for absorption. Self-adherent bandage wrap (Vet Wrap or similar) Flexible self-adherent wrap is used as the outer layer of a bandage. This material bonds to itself but doesn’t stick to fur. It’s stretchy, so it can cut off circulation if it’s applied tightly. Don’t stretch it while you’re applying it; just lay it over the top of the gauze and press gently to adhere it to itself. Adhesive bandage tape If you have self-adherent wrap, you might not need adhesive bandage tape. Adhesive tape is used to hold a bandage together. For a first aid bandage, try to avoid sticking tape to the fur. If a pet needs a bandage that’s more secure than just self-adherent wrap over gauze, the pet needs to be seen at a veterinary clinic and someone there will be taking your bandage off anyway. Don’t use Band-Aids or other adhesive bandages meant for humans. Bandage scissors Antibacterial ointment Tweezers (for removing ticks) Disposable gloves Eye wash Eye wash or sterile saline is good to have on hand if a potentially damaging liquid gets splashed into an animal’s eyes. Use care when working around an injured animal’s face, though. Towels Towels are handy for mopping up messes, creating an impromptu stretcher, or soaking in water to cool an overheated animal. Medications and other remedies Medications like pain relievers and antihistamines should only be used if a veterinarian has specifically recommended them. Many pain relievers for humans, including common nonprescription pain relievers, are not safe for pets. Some pet first aid supply lists include products to induce vomiting or poison remedies like activated charcoal. Never use products like these without consulting a veterinarian first. Inducing vomiting can be harmful. For example, caustic substances and foreign objects can damage the esophagus on the way down and again on the way back up. Photo by Alvan Nee on Unsplash Laurie Anne Walden, DVM Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Malassezia pachydermatis organisms. CDC/Janice Haney Carr. Photomicrograph of Gram-stained Malassezia pachydermatis organisms. CDC/Janice Haney Carr. Yeast skin infection (dermatitis) is common in dogs and also affects cats. Animals with allergies to pollen, grass, and other substances are especially prone to yeast dermatitis and yeast ear infections, so watch for the signs of infection if your pet gets itchy when the seasons change. Causes Yeast dermatitis is caused by Malassezia organisms on the skin. Malassezia yeasts are part of the normal collection of microorganisms that live on the skin and in the ears of animals. Yeast dermatitis occurs when something about the host animal—skin condition or immune function—causes Malassezia to overgrow or results in an abnormal immune response to Malassezia organisms. Examples of skin conditions that lead to yeast overgrowth are inflammation and increased moisture. Some animals are allergic to Malassezia and develop yeast dermatitis even when the number of organisms on the skin is relatively low. These are some of the things that increase the risk of yeast dermatitis:

Signs The most commonly affected areas are the face, neck, armpits, belly, inner thighs, feet, and ears, although yeast dermatitis can affect any part of the skin. Yeast dermatitis typically causes these signs:

Diagnosis Samples from affected areas are taken with various methods (tape pressed to the skin, a microscope slide pressed to the skin, cotton swabs, scraping with a blade, or possibly skin biopsy) and examined under a microscope. Animals with yeast dermatitis might have very few Malassezia organisms visible with a microscope. In animals with long-term or recurring yeast dermatitis, other tests are often done to look for an underlying cause. Treatment Yeast dermatitis is treated with topical medication, oral medication, or both. Topical antifungal products include shampoos, mousses, wipes, creams, and so forth. Topical products need enough skin contact time to be effective, so shampoos usually come with instructions not to rinse the lather off for at least 10 minutes. A number of prescription oral antifungal medications are also used. The choice of treatment type—topical, oral, or both—depends on the individual animal, the part of the body affected, the response to earlier treatment, and the ability of the animal’s owner to apply topical treatments. Not everyone has a place to bathe a large shaggy dog twice a week, for instance. Treatment for yeast dermatitis typically needs to continue for weeks. For animals with recurring yeast dermatitis, the underlying cause also needs to be treated. Reference 1. Bond R, Morris DO, Guillot J, et al. Biology, diagnosis and treatment of Malassezia dermatitis in dogs and cats clinical consensus guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet Dermatol. 2020;31(1):28-74. doi:10.1111/vde.12809 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/vde.12809 Public domain image source: CDC/Janice Haney Carr |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed