Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Indoor cats need mental stimulation and physical activity to stay happy and healthy. Playing games with your cat and providing cat-appropriate toys can make life better—and more fun—for both of you. When and How Long to Play Always let your cat choose whether and when to play. Cats might nip when they’re overexcited or want to stop interacting, so watch your cat’s body language (for example, pinning the ears back or twitching the tail) and be ready to end the session before things go too far. When you’re petting your cat, remove your hand every minute or so and watch her reaction. If she ignores you or walks away, it’s time to stop. If she rubs her head against your hand, she probably wants more head or face petting. Some cats are overstimulated by being touched for very long on the lower back near the tail and prefer to be petted on the front half of the body.[1] The ideal length of a play session probably depends on the individual cat. The results of a 2014 cat owner survey showed a possible link between the length of play sessions and cat problem behaviors: owners who played with their cats for at least 5 minutes at a time reported fewer problem behaviors than those who played for 1 minute at a time. However, the survey didn’t show whether longer play resulted in fewer problem behaviors or whether owners just didn’t engage as much with cats who had behavior issues.[2] Choosing Toys To choose toys and games for your cat, start by thinking like a cat. Cats are born hunters, and even cats living the good life indoors need to be able to act on their natural instincts. Cats play by acting out predator behaviors:

The toys you provide should allow your cat to perform all of the instinctive predator behaviors. Cats tend to like moving objects they can stalk, which is why your feet might be a target. Try a variety of toys that mimic the movements of prey animals like rodents and birds. These can include toy mice, balls, toys dangling from the end of a wand, or toys pulled on a string. Of course, don’t leave strings or toys your cat can swallow within your cat’s reach when you’re not there to supervise. Cats can become frustrated if they can’t catch what they’re chasing. If you use a laser pointer, hide a treat for your cat to find after stalking the moving light. (And don’t point the light into your cat’s face.) Balls inside circular tracks might not be attractive to some cats because they can’t capture, hold, or bite them. Cats get bored with their toys, so don’t leave the same toys out every day. Rotate your cat’s toys to keep her mind stimulated. You don’t have to buy a lot of cat toys to play with your cat. Paper bags, boxes, crumpled paper balls, and socks all make great toys. Think about engaging all of your cat’s senses with objects that look, smell, taste, sound, and feel different from each other. For more ideas for toys and enrichment for indoor cats, check these resources:

References 1. Delgado M. Do cats have petting preferences? Yes! Cats and Squirrels website. December 29, 2014. Accessed March 19, 2020. http://catsandsquirrels.com/pettingprefs/ 2. Strickler BL, Shull EA. An owner survey of toys, activities, and behavior problems in indoor cats. J Vet Behav. 2014;9:207-214. 3. Playing with your cat. International Cat Care. July 30, 2018. Accessed March 19, 2020. https://icatcare.org/advice/playing-with-your-cat/ Photo by Kim Davies

0 Comments

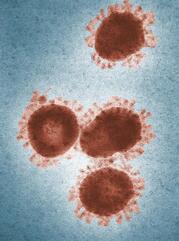

Laurie Anne Walden, DVM  Colorized transmission electron microscopy image of avian infectious bronchitis virus. Credit: CDC/Dr Fred Murphy; Sylvia Whitfield. Colorized transmission electron microscopy image of avian infectious bronchitis virus. Credit: CDC/Dr Fred Murphy; Sylvia Whitfield. Coronaviruses cause disease in many animal species. Most coronaviruses affect either the respiratory tract or the digestive system. Some coronaviruses cause no symptoms or only mild illnesses like the common cold. Others cause serious disease. New information continues to emerge about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). At this time (early March 2020), there is no evidence that this virus can spread between humans and companion animals like dogs and cats. For updated information about COVID-19, see these resources:

Coronaviruses got their name from spike proteins that cover the surface of the virus particles and look like a crown (corona in Latin) on electron microscopy images. Coronavirus spike proteins bind to receptors on the host animal’s cells and allow the virus particles to fuse with the cells. Spike proteins and the receptors they target vary according to the type of coronavirus. Because animal species don’t all have the same molecular receptors and different coronaviruses have different surface proteins, coronaviruses tend to be species specific. A coronavirus that causes disease in cows, for example, doesn’t normally cause disease in cats. This is also why your dogs don’t catch your cold even if you sneeze in their faces. Some coronaviruses are zoonotic, meaning they can be transmitted between animals and humans. Coronaviruses jump to a new host species through genetic mutation. Mutation changes the virus proteins and creates a genetically different coronavirus that can infect a different host. Jumping to a new species might also be easier if the molecular receptors in the new host species are similar to those of the original host species. Coronavirus infections in livestock and companion animals can be severe. However, until 2002, coronaviruses usually caused only mild disease in people with fully functioning immune systems. In 2002, an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) occurred in China, and in 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) emerged. Both of these outbreaks were caused by coronaviruses thought to have begun as bat viruses. Bats and people don’t have much contact, so the viruses that caused SARS and MERS spread to people through intermediate hosts: civets for SARS and camels for MERS.[1] COVID-19 is the third coronavirus disease to cause serious outcomes in humans.[2] Animal Diseases Caused by Coronaviruses Diseases caused by coronaviruses have been identified in many mammal and bird species. Some examples of coronaviruses that cause serious disease in livestock are transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in piglets, infectious bronchitis virus in chickens, and bovine coronavirus in cows.[3] The coronaviruses of most concern in cats and dogs are feline coronavirus, canine coronavirus, and canine respiratory coronavirus. Feline coronavirus usually causes such mild symptoms they aren’t noticed at all. In some cats, though, infection leads to feline infectious peritonitis, a devastating disease that is nearly always fatal. (Feline infectious peritonitis will be covered in more detail in another article.) Canine coronavirus is passed through the feces and causes vomiting and diarrhea, especially in groups of dogs in kennels and animal shelters. Infection usually carries a low risk of death, but a more severe strain of canine coronavirus can be fatal to dogs.[4] Canine respiratory coronavirus is one of the causes of canine infectious respiratory disease (kennel cough). The emergence of SARS and MERS in humans prompted more research into coronaviruses, so new therapies for coronavirus diseases may be available in the future. References 1. Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181-192. 2. Coronaviruses. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases website. Updated March 2, 2020. Accessed March 5, 2020. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/coronaviruses 3. Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1-23. 4. Decaro N, Buonavoglia C. Canine coronavirus: not only an enteric pathogen. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2011;41(6):1121-1132. Image source: https://phil.cdc.gov/Details.aspx?pid=15523 |

AuthorLaurie Anne Walden, DVM Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

The contents of this blog are for information only and should not substitute for advice from a veterinarian who has examined the animal. All blog content is copyrighted by Mallard Creek Animal Hospital and may not be copied, reproduced, transmitted, or distributed without permission.

|

- Home

- About

- Our Services

- Our Team

-

Client Education Center

- AKC: Spaying and Neutering your Puppy

- Animal Poison Control

- ASPCA Poisonous Plants

- AVMA: Spaying and Neutering your pet

- Biting Puppies

- Boarding Your Dog

- Caring for the Senior Cat

- Cats and Claws

- FDA warning - Bone treats

- Force Free Alliance of Charlotte Trainers

- Getting your Cat to the Vet - AAFP

- Holiday Hazards

- How To Feed Cats for Good Health

- How to Get the Most Out of your Annual Exam

- Indoor Cat Initiative - OSU

- Introducing Your Dog to Your Baby

- Moving Your Cat to a New Home

- Muzzle Training

- Osteoarthritis Checklist for Cats

- What To Do When You Find a Stray

- Our Online Store

- Dr. Walden's Blog

- Client Center

- Contact

- Cat Enrichment Month 2024

|

Office Hours

Monday through Friday 7:30 am to 6:00 pm

|

Mallard Creek Animal Hospital

2110 Ben Craig Dr. Suite 100

|

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by IDEXX Laboratories

RSS Feed

RSS Feed